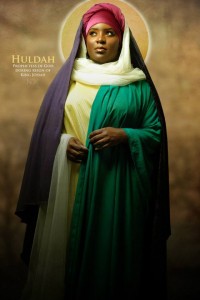

Images of the prophet Huldah by Rabbi Me’ira Iliinsky and (photo) James Lewis

Images of the prophet Huldah by Rabbi Me’ira Iliinsky and (photo) James Lewis

A recent conversation between two leading public intellectuals has brought renewed attention to the ways in which we, pastors, preachers, academics, activists, commentators and the public at large use the lexicon of the prophetic to define our work or the work of others. In my seminary classroom I am constantly stretching my students to expand their understanding of prophets, those who prophesy prophecies, and the prophecies they prophesy, beyond the predictive. In the public square, with its emphasis on social and political commentary, the understanding needs to be stretched beyond social critic or even champion of social justice or truth-teller talking back to power (or empire).

An analysis of prophecy in ancient Israel within the scope of its closest Ancient Near Eastern (ANE) corollaries demonstrates that prophets engaged in a variety of tasks, all of which were part of their prophetic portfolio. (This list and basis for my commentary here is drawn from my own work on prophets, Daughters of Miriam, which includes overviews of Israelite and ANE prophets and prophecy.) Prophetic practices include:

(1) interceding with [God] on behalf of human beings,

(2) performing musical compositions,

(3) commanding military forces,

(4) performing miracles,

(5) appointing monarchs,

(6) advising monarchs,

(7) archiving monarchal reigns,

(8) evaluating and legitimating Torah [scripture and religious/legal rulings],

(9) making, teaching, and leading disciples,

(10) mediating human disputes,

(11) archiving prophetic utterances,

(12) constructing and guarding the temple,

(13) serving as executioner,

(14) inquiring of the Divine, and

(15) proclaiming the word of [God].

Most simply, biblical prophets were divine intermediaries, facilitating communication between God and humanity at the instigation of either party. Prophets enjoyed perhaps the ultimate authority in biblical Israel given they could “fire” a monarch and appoint a new one while the previous one was still living.

One reason there is such a limited understanding of prophets and prophecy is the relative ignorance of the broader prophetic tradition in and behind Israel’s scripture. Reducing the prophetic enterprise to the men with biblical books named after them unnecessarily and inappropriately curtails the prophetic witness in limited ways. In order to know what biblical prophets do, it’s helpful to know who the biblical prophets. Explicitly identified women prophets are in bold, gender inclusive categories that could mask women prophets are italicized.)

Torah: Moses, Miriam, prophesying elders, Balaam

Prophetic Books: Deborah, Anonymous (Jdges 6:7-10), Prophetic Communities (1 Sam 10:1-13, 19:18-24); Nathan; Gad; Ahijah the Shilonite; Unnamed (1 Kgs 13, 20; 2 Kgs 9:1-13; Jehu ben Hannai, Azariah ben Oded; Elijah, Micaiah ben Imlah, Zedekiah the Canaanite, Elisha, Huldah, Isaiah, mother of Isaiah’s child(ren), Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Women’s Prophetic Community (Ezekiel 13:17-19), Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zecharaiah, Malachi (following Hebrew canon, Jewish classification in which Daniel is not a prophet)

Writings: Noadiah, Heman Family Singers (1 Chr 25:1-8), Iddo, Azariah ben Oded, Eliezer ben Dodavahu, Oded

Prophets in ancient Israel engaged in a broad range of activities. They interceded with [God] on behalf of human beings; performed musical compositions; commanded military forces; performed miracles; saw things that no one else could see; determined life expectancy; appointed monarchs; advised monarchs; archived monarchal reigns; mediated human disputes; archived prophetic utterances; validated divine proclamation; made, taught, and led disciples; constructed and guarded the temple; inquired of the divine; and proclaimed the word of [God]. The proclamation of the divine word is the dominant component of prophetic activity. The proclaimed word regularly focused on social, political, and religious matters; concern for right relations between humanity and divinity; relationships between humans; and appropriate religious practices. The receipt of the divine word was an extraordinary, extrasensory experience. Some prophets saw or envisioned the word; others experienced it intimately, literally “the word of [God] happened (hayah)” to the prophet. Some prophets experienced divine communication in more than one medium. Proclamation of the divine message was multifaceted: singing, preaching, and performing were regular modes of prophetic expression. The most common expression of prophetic utterance included the introductory formula “So says [God].” (Gafney, Daughters of Miriam, 47)

A frequent myth I regularly encounter in the public square, classroom and congregation is that all biblical prophets were male. (I’ve had to correct at least one public intellectual with a Ph.D. in a religious discipline on that point recently.) Others know better and may include Dorothy Day with Martin Luther King and Howard Thurman as modern day prophets. The idea that there are contemporary prophets is a contested notion. I find it more palatable and useful to think and speak in terms of prophetic work, action, ministry or service.

Attempts to translate Iron Age prophetic culture in to contemporary American, digital, social media culture regularly fail to take note of the theo-political context of Israelite and ANE prophecy: monarchy. A court prophet is not the same as presidential surrogate and a street prophet is not the same as a commentator who critiques both political parties – or for that matter a socially conscious rapper. While some may presume that (some) American presidents are or have been divinely appointed and elected and others wish for a theocracy, the religious role of the monarch in the ANE, including Israel has no corollary in our democracy (nor even in extant monarchies).

Regardless or one’s religious beliefs about whether prophecy or prophets exist in the world today, the biblical lexicon does not fit in the digital age in the same way as it did in the Iron Age. That is not to say that we ought give up the language, rather to point out the futility of trying to shove square peg pundits and preachers into the round holes of biblical era prophetic roles.

Yet the image and model of the biblical and ANE prophets are available for interpretation and reinterpretation. There are I contend, warrior prophets like Deborah, scholar prophets like Huldah, poet prophets like Micah, politically savvy prophets like Nathan, but perhaps more, legions of unknown prophets whose names we shall never know. Without worrying about who is a prophet (or for that matter an apostle) or legitimate heir to a prophetic mantle, women and men are simply doing the work, crying out to and for God and God’s folk.

firstfruit1

April 21, 2015 5:18 pmThanks! This is very helpful for my Introduction to Bible class.

Christy Cabaniss

September 29, 2016 8:25 amThank you, I’m looking forward to reading your work. I’m developing a Sunday school program at my church in South Carolina. I want to broaden minds and make some important connections.