In the name of God whose mercy is just and whose justice is merciful. Amen.

Zillah gave birth to Tuval Qayin, who forged every kind of implement of bronze and iron. And the sister of Tubal Qayin was Naamah.

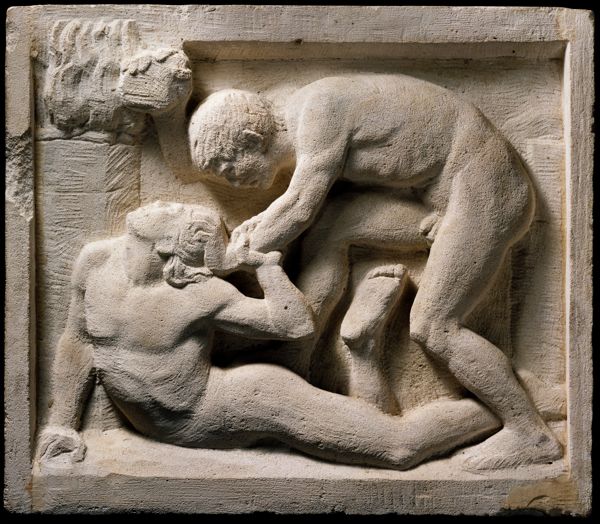

In my sanctified imagination I envision what it was like being Tuval Qayin, saddled with the name of his most infamous ancestor. Can you imagine with me and put yourself in his shoes? Tuval Qayin was the great-oh-so-many-greats-grandson of that Qayin, whom you may know as Cain. They may not have remembered all of the generations in between. But they remembered that name. Qayin. It may be startling or even disorienting to hear names with which you are familiar spelled and pronounced in ways with which you may not familiar. Womanists place a high value on naming and in my practice that means not defaulting to European names for Afro-Asiatic biblical characters. If you look up images of Qayin and Abel, you will find more than a few of a black or significantly darker Qayin murdering a white Abel. (As we say on twitter #fightme.)

Can’t you hear the folk tormenting Tuval Qayin? We know who you are. We know where you come from. We know who your people are. We know they and you ain’t ish. You Qayin’s people, and errbody knows your great-great-whatever-granddaddy was a murderer. He merked his own brother. You one of them. Add to that his own father would become infamous for killing a man himself. Folk would say the apple don’t fall far from the tree. Tuval Qayin never stood a chance. Anything he ever did wrong, folk would point back to his people–never mind that most of his family weren’t murders, but two was two too many.

And then there was his parents’ marriage. His father Lamech was a poster boy for the patriarchy. He is credited with inventing polygamy because he wanted more. As a side note, Lamech’s invention of polygamy presents a challenge for biblical marriage enthusiasts and literalists–some of them anyway; others are far too excited by the prospects. On the other hand, Lamech’s redefinition of marriage was not only not challenged by God but eventually accepted and normalized providing an unexpected biblical model for the intentional crafting and redefinition of marriage norms.

Nevertheless, I don’t imagine it went over well with the neighbors: Your daddy ain’t nothing (and your mama ain’t much, neither one of them). Tuval Qayin and his siblings were the first to have two mommies, and if our more recent history is any example, he would have been teased mercilessly because his family was different. And if human beings haven’t really changed that much in the past five thousand years, some folk may have been violently opposed to Lamech’s marriage and meted that out upon the most vulnerable members of his family, particularly the boy with the OG murderer’s name.

And the thing was, they weren’t wrong about Qayin. Qayin was a murderer. A fratricide. A brother killer. He was guilty. He did it. One of the hard truths of this world is that even in an unjust justice system some folk locked up are guilty. Somebody’s son, father, uncle, cousin, brother, sister, mother, daughter, auntie is locked up and locked down because they did it, whatever it was. And some folk want to throw them away forever, use them for cheap labor, profit off of their bodies, throw their bodies at forest fires, leave them behind to die in hurricanes, and if they make it out, make it darn near impossible for them to find legal work to support themselves and their families. Especially if they’re black or brown. And then as the icing on the cake, strip their voting rights from them so they can’t help reform the system that they know better than anyone else. Everybody ain’t innocent and even when they are the privilege of innocence ain’t extended to everybody. Some folk are guilty as charged. Qayin was caught red-handed. The red was literally and literarily the blood of his brother, the brother he murdered with his own hands. Qayin destroyed a life with an act of horrific violence and that violence had repercussions.

Qayin’s act would have destroyed more than one life; the lives of his parents who were also the parents of his victim would have also been devastated. In the narrative world of Genesis there were only a handful of people around–don’t ask me where he got his wife; the narrator isn’t interested in a seamless story. Qayin’s actions impacted all of them. You could say his crime shook and shaped the entire world. If ever there was a candidate for original sin, this would be it. The text actually uses the word sin here; it is the first time the word appears in the canon. Eating forbidden fruit in pursuit of wisdom doesn’t qualify, but that is another sermon. Qayin also changed the course of his own life. It was circumscribed by the choice he made. There was no denying it; no boys will be boys, no unjust judge, no biased jury.

Qayin was like a lot of guilty folk. He was responsible for his choices and their consequences. He had a price to pay and he paid it. And at the same time, he was also a product of circumstances that seemed designed to set him up to fail. The story tells us flat out that God has biases, or if that’s too strong for you, preferences. God prefers brisket to broccoli. Who doesn’t? The narrator’s unvarnished account of God’s preference makes it sound like there was nothing Qayin could have done to make his offering acceptable. Perhaps one way of reading God’s preference is that it represents the structural inequity into Qayin and Hevel were born, into which we were all born. Hevel was born into privilege and Qayin was born into peril. That’s not a good look on God so interpreters have worked overtime blaming Qayin for bringing second rate crops though the text says no such thing. So what then, within the confines of the story, could Qayin have done differently?

Qayin wasn’t responsible for the circumstances in which he found himself. He was responsible for the choice he made. Sometimes we find ourselves on the wrong side of circumstances we can’t control. And it sure seems like God is either actively against us or refusing to help us. Structural inequity isn’t an excuse, but it is a contributing factor. Did Qayin have to tools to overcome his structural disadvantage? Did his parents have the talk with him, teaching him how to navigate the meat-loving world as a grain-gatherer? Or were they too caught up in their own drama to see that one of their boys was different from dominant culture expectations? I don’t think any of us are that far removed from Qayin given the right circumstances. Surely you’ve noticed how much more violent our world seems to be.

Folk are quick to speak violent words and raise violent hands. And violence begets violence. Everywhere I look I see violence: violent rhetoric, violent encounters with police, violence against women, violence against children, violent theologies, violence against gay folk, violence against trans folk, violence against the earth and her creatures, violent government domestic policies, violent government international policies, violent economic policies.

Now I have been raised as a bible reader to view Qayin with contempt, and in some settings to view the mark of Qayin as the imposition of vampirism–but that too is another sermon, or perhaps an elective. And yet in the previous century when I was a seminarian, I learned to question the way I always read and to read from the position of characters with whom I didn’t hold any sympathy, who were not, or were not supposed to be, God’s people in the text–people like Qayin and peoples like the Canaanites, Jezebel and Jephthah, Pharaoh and Potiphar’s wife, Qayin and those who bore his mark, whether in their flesh like Qayin or in their name like Tuval Qayin.

It’s hard for some of us to read from Qayin’s point of view. Most of us can say we have never killed. Qayin’s killing of Hevel represents more than the commission of murder; it is also the first act of violence committed by a one person against another in the world that Genesis crafts for us. Let us not deceive ourselves that we cannot also be Qayin because we may not have killed. Qayin’s repertoire of violence was severely limited; ours is much broader. Qayin embodies all of the violence of which we are all capable and which some of us have indeed committed.

Let me be honest in one particular regard it’s hard for me to preach from Qayin’s perspective at the present moment. I have hierarchies of with which guilty folk I can be sympathetic. My rage at men who violate women’s bodies is not interested in their redemption. (I just thought I should tell the truth today.) But unlike those men who evade the consequences of their actions, Qayin served his sentence. Qayin lived with the consequences of his actions for the rest of his life. And that ought to be enough. But not for some folk. There are folk who will never let Qayin or anyone associated with him forget what he did that one time. Nothing else matters. No mark necessary.

Some folk hold onto Qayin’s crime out of their deep grief. Others simply refuse to see beyond the worst moment and worst choice of his life. And our contemporary conversations about forgiveness are of little use. I watch as victims and survivors, often marginalized people targeted by folk who wield power individually or societally, are urged and shamed into making immediate statements of forgiveness before they’ve even processed their loss to be model Christians so as not to burden the white supremacist bomber or trigger-happy cop with their unforgiveness. All too often we’re given a false choice in what is passing for forgiveness these days: we’re told to forget about what is past in the same breath in which we’re told it didn’t happen or we can’t remember, and the other option is ruining someone’s life by holding what they’ve done or are accused of doing over their heads for the rest of their lives. Neither of these is satisfying. Neither involves confession or reparation and where no reparation can be made, conviction and execution of a just sentence, but above all and before all repentance. Not bold-faced lies and denials or lawyer-crafted PR statements admitting nothing and saying less.

Qayin is a felon and he is also one of us. But unlike those who have never been held to account for what they have done, Qayin paid the price and served his time. Like many felons, he would never be able to live down the infamy of his name or his crime. And like other felons, he is more than the worst thing he had ever done. Qayin murdered his brother. He failed miserably at being his brother’s keeper. But we don’t get to wash our hands of him. We are still Qayin’s keeper. Some of us have been falling down on the job. Some of us don’t want that job. Some of us are using our grief about Hevel to justify abandoning Qayin to the aftermath of his bad decisions and the circumstances from which he was unable to extricate himself. But you know who didn’t abandon Qayin? God.

God accompanied Qayin into exile to hold the rest of the world to account for how they treated Qayin as much as to hold Qayin accountable. Qayin was still God’s child. God is with Qayin as he rebuilds his life. He marries and becomes a father, signaling his readmittance to society. He makes something of himself. He builds a city and names it after his child, not himself as other women and men city-builders would do. In so doing he makes his life’s work about the generations to come. And let’s hear it for the unnamed sister who took a chance on a man with a bad name.

It was that bad name with which I imagine Tuval Qayin was taunted. He was Qayin’s fifth-generation descendant gifted with Qayin’s name as his own. He and his brothers by another mother, Yuval and Yaval, lived with that legacy and they transformed it. The passage in which they occur is both genealogy and etiology. Yuval ben Adah brought gifts of wind instruments and stringed instruments into the world. And Tuval Qayin ben Zillah, the boy with the bad name, brought metallurgy and manufacturing to the world.

Throwing away Qayin would have meant throwing away all that he and his descendants produced and achieved, including Tuval Qayin, Yuval and Yaval and their sister Naamah. Throwing them away would have cost the world pillars of civilization as the ancient Israelites conceived it: music and the arts and cutting age technology. Without Qayin or Tuval Qayin there would have been no Prince or B.B. King, no Sister Rosetta Thorpe or Alicia Keys, no Alex Byrd or Yo Yo Ma.

God didn’t throw away Qayin. God didn’t even take his life. God created space for him to live into who he could be while living with who he was, and the world is the better for it. There are folk I want to throw away. There are folk through whom I can’t imagine–even within the realm of my sanctified imagination–that there will ever be any worthwhile contribution to our world from them or their spawn. Their hands are every bit as bloody as Qayin’s. But I believe in a God whose mercy is just and whose justice is merciful. The God who heard Hevel’s blood cry from the earth is also the God who kept Qayin. The God who cares for Qayin is the God who demands justice for Hevel.

God’s justice is as inescapable as God’s mercy, is as inescapable as God, God with us, God with even Qayin. That same God became a child, begotten, birthed, breastfed, bathed, baptized, and buried. God came to us in our own failing and fragile human flesh. In living, in loving, in healing, in teaching, in dying, in rising God in Jesus is the God who will not abandon us to our circumstances, our choices, or their consequences. The God who sentenced Qayin is the God who keeps Qayin, leaving us to wrestle with what it means to be the keeper of kinfolk in these days. Amen.

Genesis 4:1Now the human had known his woman Chava, Eve, and she conceived and gave birth to Qayin, Cain, saying, “I have crafted a person with the Creator of Heaven and Earth.”2Then she went again to give birth, to his brother Hevel, Abel. Now Hevel was a shepherd of the flock, and Qayin a cultivator of the ground. 3And it was after some days Qayin brought to Earth’s Creatoran offering of the fruit of the ground, 4and Hevel brought some of the firstborn ewes of his flock, and their fat portions. And the God Who Chooseshad regard for Hevel and his offering, 5but for Qayin and his offering the Inscrutable Godhad no regard. So Qayin was very angry, and his face fell. 6The God Who Attendssaid to Qayin, “Why are you angry, and why has your face fallen?7If you do well, will it not ascend? And if you do not do well, at the opening sin reclines; its desire directed towards you, but you will master it.”

8Then Qayin said something to his brother Hevel; now they had gone into the field. And when they were in the field Qayin rose up against his brother Hevel and killed him. 9Then theGod of All Fleshsaid to Qayin, “Where is your brother Hevel?” He said, “I don’t know; am I my brother’s keeper?” 10Then the Just Godasked, “What have you done? A voice…your brother’s blood-spills are crying out to me from the ground! 11And now cursed are you from the ground, which has opened her mouth to receive your brother’s blood-spills from your hand. 12Therefore, when you cultivate the earth, she will no longer yield to you her strength; you will be one who wanders and staggers throughout the earth.” 13Qayin said to the Gracious God, “My punishment is greater than I can bear! 14Look! Today you have driven me away from the soil on the face of the earth, and I shall be hidden from your face; I shall be one who wanders and staggers throughout the earth, and anyone who meets me will kill me.” 15Then the God Who Hearssaid to him, “It shall not be so! Upon anyone who kills Qayin there will be sevenfold vengeance.” And the God Who Watchesput a mark on Qayin, so that no one who came upon him would kill him. 16Then Qayin went out from the presence of the God Who Saves, and settled in the land of Wandering called Nod, east of Eden.

17Qayin knew his woman, and she conceived and gave birth to Chanokh, Enoch; and he built a city, and named it Chanokh after his child Chanokh. 18Born to Chanokh was Irad; and Irad fathered Mehuyael, and Mehuyael (Mehijael) fathered Methushael, and Methushael fathered Lemech, (Lamech). 19Lemech took two women; the name of the one was Adah, and the name of the second Zillah. 20Adah gave birth to Yaval; he was the ancestor of those who live in tents surrounded by livestock. 21Yaval’s brother’s name was Yuval; he was the ancestor of all those who take up the lyre and pipe. 22Then Zillah gave birth to Tuval Qayin, who forged every kind of implement of bronze and iron. And thesister of Tuval Qayin was Naamah.

Translation, the Rev. Wil Gafney, PhD

Terrance L Thomas

October 23, 2018 5:39 pmA profound read…and gives me one to think about as I process my CPE supervisory work.

Thank you.

Fred Scherlinder Dobb

October 24, 2018 10:48 amFreaking brilliant, an imperative read. (And this from someone who prefers broccoli over brisket). Thanks so much for this timely Torah. I’ve been highlighting your Womanist Midrash in our congregation, and will add this and other blog posts to it. Todah rabbah; blessings…

Gayle Fisher-Stewart

October 25, 2018 8:00 amOMG! I love this! When will you be on the east coast or perhaps I can just invite you to come and preach!

Womengoforward

November 3, 2019 8:50 pmThank you for sharing God’s light in you to some of us who are seeking

LaMonte Kendrick

September 27, 2023 10:09 pmThank you for the thorough insightsive view point. As a historian and student of biblio text I found your perception of the Hebrew/ Aramaic influences very interesting.. it is interesting to see the scholastic angles that are rarely considered whereby the geological perspective and chronological consideration are apply in it proper text that to colorize the orgin of biblical content on a European construct. It is very difficult to precieve, to understand and to imagine how the decendants o f pagans , foreign association and of recent assimilation can be so gift in the full knowledge of that they were only recently introduced to. And now they have renamed , chronicle, and have declared ownership.

But as a historian, I have come to the conclusion it is all about controlling and power. Just as in the case of Egypt, how throughout the course of history Europeans have considered Africa as the dark continent and nothing worth noting has come from it. Time has began to turn it pages and revealing the Orgin of man kind and civilization. And now the orgin of man has been exposed as in the book of Genesis as only a soul that capable of producing the sum of all mankind, an African, in modern terms a Blackman, thank you.