Exodus 1:1 These are the names (shemoth) of the sons of Yisra’el who came into Egypt with Ya‘akov…

Exodus 1:1 These are the names (shemoth) of the sons of Yisra’el who came into Egypt with Ya‘akov…

Baniym can of course mean “sons” or “children” and usually I err on the side of inclusion. But in this text, it is clear that only male progeny are indicated, demonstrated by the list of names that follow. These are the names of Israel’s sons, but what about his daughters?

5 So it was that all the souls, the ones who went out from Ya‘akov’s loin, יוצאי ירך יעקב, were seventy souls.

“The ones who exited, went out” – dare I say “squirted out”? – of Jacob’s singular loin, a euphemism for the specific male organ rather than “genitals” in general usually indicated by the plural or “thigh” when ירךis singular in other contexts, were seventy souls. There are twelve names given for those sons in v 1 and seventy souls altogether in v 5. Perhaps then, Jacob had fifty-eight daughters with Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah – the text being clear that Rachel had only Benjamin and died giving birth to him. Who were these fifty-eight benei-or perhaps better-banoth-Ya‘akov? We know Dinah’s name. What about the other fifty-seven? Were they all daughters or were there lesser sons deemed insignificant by the authors of the text?

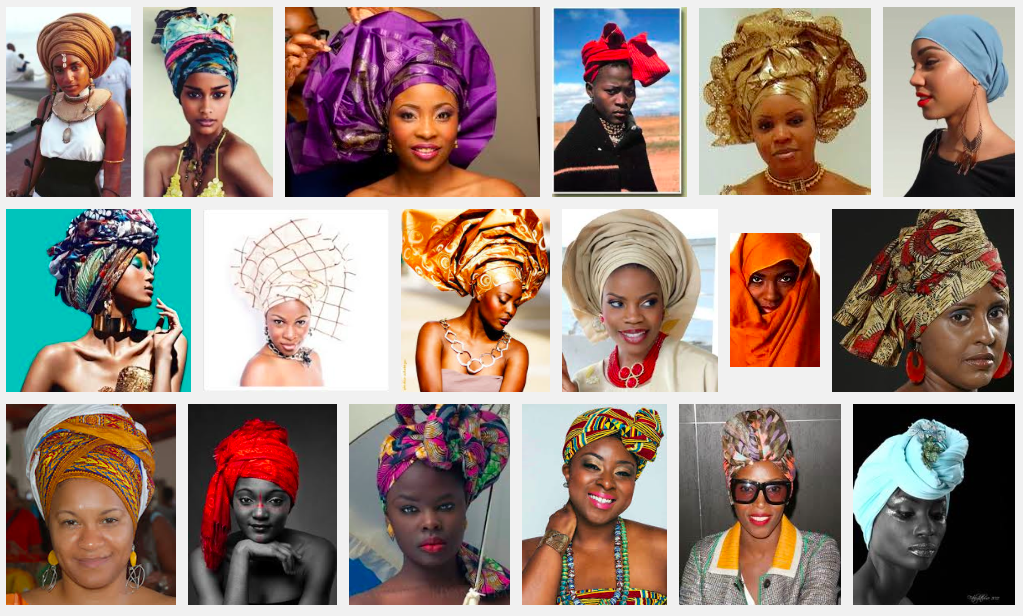

Today I’d like to reflect on the stories of Shemoth from the perspective of Jacob’s daughters, daughters-in-law and the other women whose stories become intertwined with those of Israel: Shiphrah, Puah, Yocheved, Miriam, an African princess, nearly invisible servant girls, Zipporah and her seven shepherding sisters – and their mother along with the daughters of Israel…

In response to this prompt the Dorshei Derekh Minyan engaged with me in some contemporary midrash – not bound to the rules of the classical schools – but allowing ourselves to retell the sacred stories in order to ask questions of and answer questions left by the Torah.

Here are some of the fruits of our sanctified imaginations (to use the language of the Black Church):

- Were Shiphrah and Puah Hebrew women or women who provided midwifery services for the Hebrew people? (The Hebrew is ambiguous.)Their names are Semitic: Shiphrah’s name is sh-ph-r, “to be beautiful” in Hebrew and “to be pleasing” in Aramaic; perhaps sapphire. Puah’s name might be Ugaritic for “girl-child,” like Nina in Spanish and Walidah in Arabic.

- What does it mean that Pharoah spoke to Shiphrah and Puah in person? Did he know them? How did he know them or know of them? What did it mean for them to speak to a man who was a living god in their world?

- Was the Egyptian princess who became Moshe’s adoptive mother infertile? (Was she even married?) Did Moses grow up alone, a child among adults in a palatial home?

- Did Yocheved, Moshe’s mother, arrange for him to be taught the ways of his people after she weaned him? Did she recommend a tutor? Did she and the princess collaborate in raising him? Did she send Miryam in to be his teacher? Did Miryam send herself in to be Moshe’s teacher? (How many years were there between Miryam and Moshe? – enough that Miryam was old enough to watch over her baby brother: 5, 10, more?)

- How did Yocheved’s experience growing up in Egypt watching things go from bad to worse after one Pharoah with whom her people had good relations was replced by one who would seek to anihilate them all affect her choices? It strikes me that Yocheved prefigures European Holocaust victims, watching the governments and people they knew turn into monsters whom they no longer knew or recognized. Then Yocheved became an agent of resistance: the very decision to give birth was an act of defiance.

- Yocheved’s experience, trying to maintain family unity as a slave-woman – albeit one with a beneficent mistress – was comparable to the experiences of enslaved African women in the American south, regularly separated from spouses and children, even if they labored on the same plantation. Indeed the experience of Moshe having more than one mother has ongoing corollaries in many African diasporic contexts where mothering is not limited to women who give birth. Many black churches in the Americas celebrate birth mothers, adoptive mothers, foster mothers, heart-mothers, other-mothers and single fathers on Mother’s Day.

- What happened in Moshe’s life in exile that prepared him for his encounter with the Burning Bush and for leadership. How did the hotheaded murderer become patient enough to observe that the Burning Bush was not being consumed?

- What effect did Zipporah’s worship of the God whose Name Moshe did not know have in preparing Moshe to fulfill his vocation? What on earth is going on when God later tries to kill Moshe – I call it a Divine Drive-By – and Zipporah has to stave God off with a penile blood offering.

- What’s going on in Moshe’s family that he sends his wife Zipporah away – divorcing her – takes them back when her father brings them back to him but doesn’t speak to them again in the text? Why are the biblical authors unclear about how to spell the name of Moshe’s yonder son? Why does their family virtually disappear from the pages of scripture?

- When the tribes are arrayed before the Presence of God with the tents of Aaron and Moshe in the front, in the vanguard of the tents of Levi, where is Miryam’s tent? Isn’t she in the vanguard with them?

Today, Shabbat Shemoth, Sabbath of the Names, we remembered that not all names are named in the scriptures. We looked for their stories if not their names in the text, behind the text and in the spaces in and between the words in the text. And when necessary, we named them ourselves. Shabbat shalom. שבת שלם

Leave a Comment