Shabbat Mishpatim & Shabbat Shekalim 5772

On this Shabbat that we examine toroth, laws, that we hope are rooted in mishpat, justice I offer my mechatzi shekalim, my half-shekel, my two cents on this double-shabbat.

Imagine with me. We are our ancestors. We have been liberated from Egyptian slavery. There are Israelites and Nubians and Phoenicians and peoples from every nation conquered by the Egyptians, perhaps even a few Egyptians in the great Exodus. We are all looking for a new start. We have been on this journey long enough that we’re taking it for granted. We no longer wonder where we are when we wake up. The miraculous events of the past few weeks seem like a dream except the pillar of cloud is there and there is rumbling from heaven whenever Moshe goes in to the Mishkan. We have the water and food we need each day even though we are in a desert with no oasis in sight.

From time to time Moshe comes to us with Torah, words of teaching from God of Fire and Cloud who accompanies and guides us. God and Moshe are teaching us how to be a people, how to govern and conduct ourselves, how to treat others and how to revere God, so that when we get to freedom in our new home, we will know how to live, not as the Egyptians live, not as any of the other nations of earth live, but we will model a new way of living, we think, we hope. And yes, there are other nations with codes of law and we have some laws in common, but ours is special, different, singular, like our one God.

Those of us on this journey were born in slavery as were our parents and their parents before them, generation after generation. The freedom of this journey is the only freedom any of us have ever known. We can scarcely imagine what it would be like to have land, vines and fig trees, sheep and goats, our own homes with our families, to labor for ourselves and our community, to be free of the brutality and ravishment – but we don’t talk about that. We speak of our enslavement without ever mentioning how women and girls are treated by the slaveholders of every time and place, and sometimes boys and men as well. We tell the story of Yosef who got away from that evil woman, but we never mention those who did not escape their predators.

Today, Moshe’s words include something that we thought we’d never hear again. Some of us will be sold back into slavery. And there will be no escape, no Exodus. Lo tetze. She shall not go out. There shall be no Exodus, no liberation, no freedom for her.

Exodus 21:7 When a man sells his daughter as a slave, lo tetze, she shall not go out as the male slaves go out. 8 If she is unacceptable in the sight of her lord, who designated her for himself, then he shall let her be ransomed; he shall not sell her to a foreign people – he does not have the authority to do so because of his treachery against her. 9 If he designates her for his son, he shall treat her justly as a daughter. 10 If he takes another woman for himself, he shall not diminish the food, clothing, or intercourse of the first woman. 11 And if he does not do these three things for her, she shall go out for nothing – no money.

In Exodus 20-23 the treatment of Israelite and non-Israelite slaves is repeatedly addressed. The passage begins (Ex 20:10) and ends (Ex 23:12) with Shabbat rest for the Israelites, their livestock and any resident aliens within their midst; the call for Shabbat is universal. Yet there is an omission of the free women in the household.

Ex 21:7-11 speaks of unmarried women and girls who are sold into slavery by their own fathers, (or perhaps parents), setting this Torah in the middle of the Exodus journey, allowing for the literary possibility that some young women left Egypt as freedwomen but were sold off along the way or entered Canaan as slaves. Their own fathers nullified the freedom that God gave them through Moshe, for money. A critical reading of this text looks at this passage in light of its much later composition, and sees it speaking to a period of desperate poverty in Judea, perhaps after the restoration as in Neh 5:5 Now our flesh is the same as that of our kindred; our children are the same as their children; and yet we are forcing our sons and daughters to be slaves, and some of our daughters have been ravished; we are powerless, and our fields and vineyards now belong to others.”

But this torah isn’t set in Nehemiah. It is plumb in the middle of Exodus. My first question is how are we to understand this torah in its literary context? Why would a father newly freed from slavery sell his daughter? It is striking that the text doesn’t require the family to be in debt, he can just sell her at a whim. Perhaps the best thing that I can say about this text is that it was revised in the canon, Deuteronomy 15:12-18 grants release to these enslaved women in the same circumstances as enslaved men and sens them both out with resources to help them establish themselves in the world.

Since yatza is the primary verb of the Exodus, I hear the “going out” as emancipation – but in this case, denial of emancipation, from slavery. In other words, women and girls who are sold into slavery shall not be released from bondage except as specified in this text. Yet there are some slight protections for her: The man her father sells her to cannot use her sexually and then sell her to non-Israelites. It seems he must be an Israelite himself. Her buyer cannot use her sexually if he designates her for his son’s sexual use and he cannot reduce her material provisions – food, clothing and the opportunity to conceive – if he acquires another woman. While these provisions leave much to be desired, they are clearly aimed at preventing sexual use and abandonment of vulnerable women having been sold by their fathers. I think that the very existence of this passage indicates that this is exactly what was going on, that girls were being sold, used sexually and then resold. The text refers to this as “treachery” “against” or “in” her, bevigdo-vah. The penalty – if one can call it that – for the slaveholder who does any of these things is that he forfeits all rights to the woman or girl. Verse 8 says that her enslaver shall let her be ransomed; it is not clear who will ransom her. It is hard to imagine her father buying her back.

Lastly, verse 11 says that the emancipated woman shall go out “for nothing, chinam,” “no money, ayin keseph,” that is, if someone does ransom her from slavery. She will not plunder her former enslaver as did the Israelite women plundered the Egyptians, and she will not be led to a land flowing with milk and honey. She will be on her own to make her own way in a world that may not value a formerly enslaved woman with a sexual history.

The fate of these women slaves, whether or not they are eligible for this conditional emancipation depends entirely on whether they “please” their lords or better, “if she is ra‘ah in his eyes.” So then if the woman sold by her father is not attractive to her new owner and he has sex with her anyway and then decides to get rid of her then the provisions of Ex 21:7-11 come into play. However, according to the logic of the text, if the slaveholder refrains from having sex with her, then he can sell her to a foreigner or give her to his son for his sexual and reproductive use. Then, lo tetze, she shall not go out to freedom.

My questions: How are we to understand this torah in its literary context? How does the tradition value individuals in relationship to the community? Then, reading beyond it’s context into our own, there is a belief that some people have the right to dominate and control the bodies of other people. This notion is fundamental to the scriptures but older than them even though it is sanctified by them – and by the scriptures of many if not all religions. The radical patriarchy assumed by the text is not a thing of the past. Men (and women) still sell their daughters. Some due to extreme poverty, others out of greed or addiction. Contemporary sex-trafficking and slavery keep this torah relevant. How do we fight the assumptions of this text as patriarchy continues to infect our public, religious and political discourses.

Lastly, I’d like to suggest that perhaps, Moshe’s promulgation of patriarchal toroth in the Divine Name, had something to do with his being barred from setting foot in the Promised Land. Perhaps. Shabbat shalom.

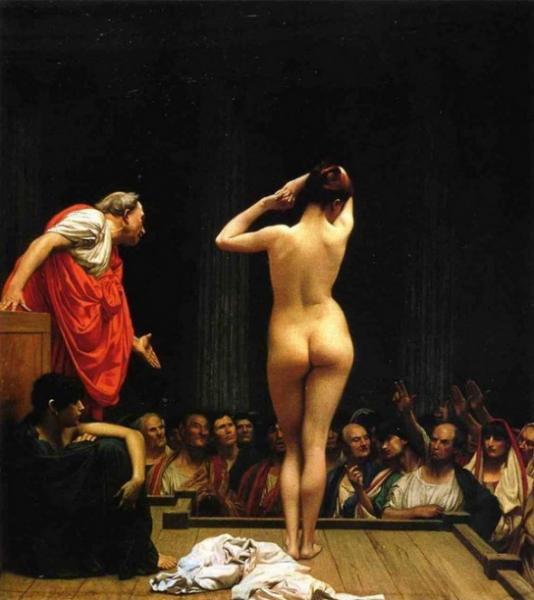

(The image: Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904): "Selling Slaves in Rome," Public Domain Photos)

Leave a Comment