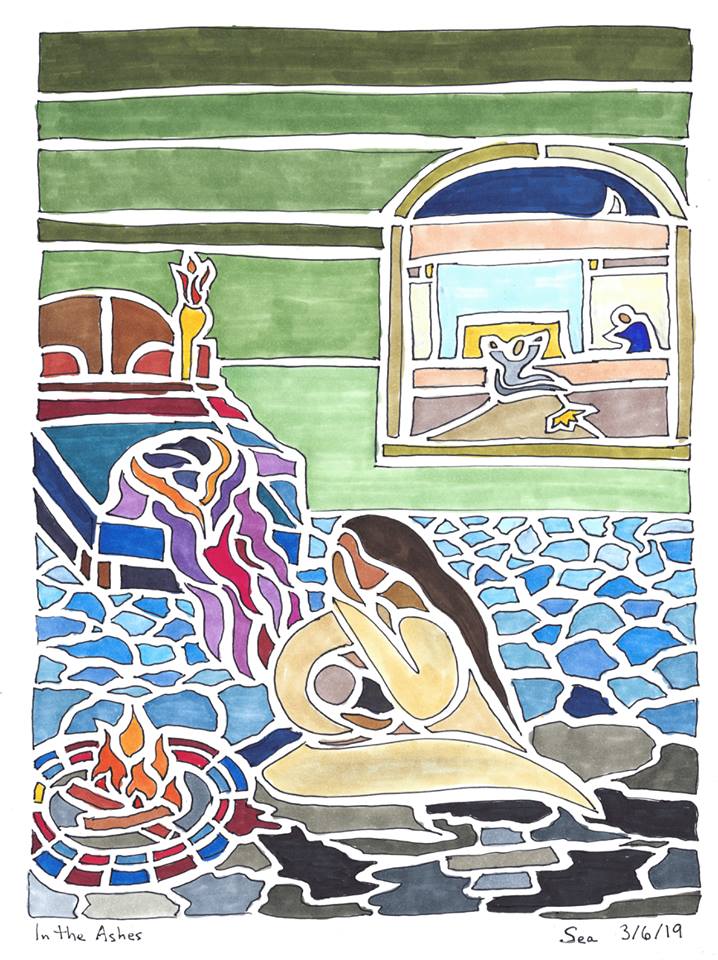

In the powerful image by Pauline Williamson (who creates as Sea), Bathsheba sits with her dead or dying child produced from David’s rape while he prays for the child. See her own interpretive work on this passage here.

It is Shrove Tuesday, the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday when Christians traditionally went to confession and were shriven, and celebrated the sweetness they would deny in Lent with delicacies or full-on Mardi Gras and Carnival. Some of us still go to confession; now we call it the Sacrament of Reconciliation or Reconciling a Penitent.

Perhaps we need to repent for how we have ritualized Bathsheba’s rape while excluding her from the penitence it generated while the bodies of women and girls (and not just) are still being plundered, desecrated, and profaned in the church and by anointed leaders.

Tomorrow is Ash Wednesday and Psalm 51 will be our corporate litany. It is ostensibly David’s psalm of repentance after his abduction, rape, and forced impregnation of Bathsheba, and his subsequent murder of her husband. Yet he does not mention her or his specific transgressions against her in it. To be fair, the biblical text constructs David’s sin as being against God and Uriah, her husband, but not against her.

A titular verse likely from the hand of an editor – and it is questionable whether a shepherd boy turned bandit possessed the literacy to write a psalm though he could have composed it and had it recorded – a titular verse proclaims the context of the psalm as that time he “went to” Bathsheba: When Nathan the prophet went to him on account of his going to Bathsheba. (my translation)

He didn’t go to her. He had her brought to him. “His going to her” is perhaps supposed to evoke a Hebrew euphemism for intercourse. It does not describe her as an active participant, an adulteress, as many would later wrongly claim. But it does not make clear the nature of his crimes.

In the (Episcopal) Book of Common Prayer, the psalm appears without the superscription so no reference to Bathsheba remains, misleading, fallacious, or otherwise. We will in David’s voice confess to sinning against God alone, with no specificity (unlike our Jewish kin who collective own a litany of transgressions on Yom Kippur).

In the Litany of Penance that follows we will confess our transgressions against others. But it is striking that we have so abstracted Psalm 51. Now that we are really talking about sexual violence and harassment in and out of the church, #MeToo and #ChurchToo, and calling once beloved figures to account for their sexual predations – Bill Cosby, R. Kelly, Michael Jackson – and laicizing priests, bishops, and cardinals, perhaps we should stop allowing David to get away with structuring his act of contrition around an abstract concept and tell him to leave his gift on the altar and first make peace with his sister.

And perhaps we should repent for our treatment of the survivors of rape in and out of scripture, our coddling of rapists, our refusal to hold great men accountable, and our love of occasionally disembodied liturgy.

In the spirit of Phyllis Trible, when we pray Psalm 51 as our prayer of repentance, we plead the blood of Bathsheba:

She was wounded for our transgressions,

crushed for our iniquities;

upon her was the punishment that made us whole,

and by her bruises we are healed.

For more on Bathsheba’s story see: Womanist Midrash.

Valerie Miles-Tribble

March 5, 2019 1:12 pmThank you for this Dr. Wil.

Michelle Alexander

March 7, 2019 10:25 amVery powerful. Thank you.