Shabbat B’ha’alotkha 25 May 2013/16 Sivan 5773

בְּהַעֲלֹתְךָ

בְּהַעֲלֹתְךָ “When you set up (the stuff)…” There’s a lot of stuff in this parsha.

The purpose of this setting up in 8:1 is to give light, so too I hope will this drash. Let’s shine the light on some of the stuff in the text. First there is the consecration of the Levites who are frequently invoked as a trope for contemporary clergy in Judaism and Christianity. As chance would have it, seminarians at RRC and LTSP are in graduation and ordination season (less closely linked for Christians). Some may well turn to these texts for inspiration, for contemplation, for liturgical innovation. But I don’t think any will turn to Numbers 8:7 and shave their entire body in preparation.

Another place for illumination in this parsha is הֶעָנָן, the cloud in 9:15. This is one of my favorite articulations of God in the text: God is present. God is visible. God accompanies God’s people. Technically God leads God’s people but when they won’t follow, God comes back for them, waits for them, attends them. That’s what happens in ch 11, the reason I asked for this parsha although I guess there wasn’t much of a bidding war.

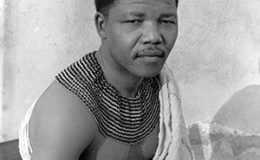

This is one of my favorite stories about Moshe Rabbenu. And I like Moshe – even though I critique him severely for failing to give Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah their inheritance as commanded by God, going to his death in disobedience on that score – I like Moses; I do.

I love that when he was on the run from a murder beef and had every reason to think about himself to the exclusion of all others, hi risked his own life and freedom for women he didn’t know because they needed help. And in the wilderness wandering, Moses interceded with God for the Israelites over and over again, even when they were cussing him and blaming him. Honestly, if I had been Moses that time God said, “Move over there. I’m going to kill them all and start over.” I’d have said, “Here good?” I would not have gotten between God and the folk while God was in a smiting mood waving incense in God’s invisible nose – how did he know which way God was facing? – hoping to calm (sedate?) God as Moshe did in 16:43.

Moses models an aggressive form of intercession: Going toe-to-(invisible)toe with God. Getting in God’s face – or at least her space. And She is she in this text, perhaps more so than in any other text.

Numbers 11 begins with the people grumbling to themselves as indicated by the hitpaal. (This text offers plenty of light for my fellow Hebrew grammar nerds.) Even though they are grumbling to themselves, God hears them and fries them. God is in a smiting mood. And Moses intercedes. Then the people grumble (again), this time craving-a-craving and weeping. And Mother God feeds her babies – more like toddlers. But they don’t want what she cooked – מָה נָא, what is this? מָה, the “what,” was not what they wanted. They wanted what they used eat for free – except it wasn’t free – before they were forced on this family road trip – except they weren’t forced.

Then God gets burning hot (again), וַיִּחַר־אַף. Literally, God’s nose was on fire.

I imagine smoke pouring out of God’s nostrils because that snorting bull image is never far away since an aleph in paleo-Hebrew is a bull’s head meaning every time someone wrote el or elohiym before the adoption of the Assyrian square script, they started with a bull (you can also see the origin of our “A”).

(You don’t know how happy I am to have found a free True Type paleo-Hebrew font that works on a Mac!) Or maybe God is just red in the invisible face. And it was in the sight of Moses, רָע, bad, wicked, evil, naughty.

Moses standing in judgment of God? That messes with my Christian sensibilities. But what I love about Job is his gumption to sue God – as a Gentile no less. So, OK, Moses is not pleased with the sight of God’s anger. Question 1) What does it look like when God is angry? Some decidedly unchristian folk say that natural disasters are what it looks like when God is angry. Ancient folk without malice thought that too. What does it look like when God is angry? What did Moses see?

In v 11 Moses has had enough – of whatever: Why are you doing me dirty? That’s how I translate it when רע)ע) is a verb. Verse 12 (follow along): Did I conceive these people? No you did. I don’t have the parts! Did I give birth to them? No you did. I don’t have the parts! Because you said to me, carry them in your bosom like a milk-nurse. I don’t have bosoms! You know what, I have had it with your whiny brats. JPS translates בכה, weep, in v 13 as “whine.” I tell you what Lady, if you are going to treat me like this kill me now.

In v 15 Moshe uses the feminine pronoun אַתְּ rather than the masculine one, אַתָּה, for God. There is an obscure point of Biblical Hebrew grammar in which the second person masculine singular takes on the form of the second person feminine singular, generally at the midpoint (atnachta) or end of a pasuq. Allegedly because of a change in inflection. I’ve always been suspicious of it because it doesn’t affect any other forms. Even if that rule is valid, it doesn’t apply here. The pronoun in question is not at the middle or end of the verse. Moses has called God a woman, or better contextually, a mother, one who needs to come get her kids.

Moses talks about being God’s unwilling male-nanny but not having the parts for the job. Question 2) What is Moses’ role in the analogy he crafts? Is he Israel’s nanny? Or Israel’s step-father? What is his relationship to God in the analogy?

Finally, what about God’s parts – and bosoms? According to Job 38:29 God does have a womb and give birth to ice and snow among other things. In Deuteronomy 32:18 Moshe will later say – or at least the torah will say he said – that God writhed in labor with us and gave birth to us. The divine Name Shaddai is rooted in “breastedness,” – see Gen 49:25 when Shaddai provides the blessings of breast (shad) and womb. Perhaps the source of all those “taste and see verses” and the Christian injunction to consume “spiritual milk” in 1 Pet 2:2.

Question 3) What if anything does gendered language in Biblical Hebrew mean? Is there a relationship between grammatical and ideological or functional gender?

The last chapter, 12, in the parsha is the one in which Miryam HaNeviah challenges Moshe and perhaps God on the perception that Moses is the only prophet in Israel while he is scandalizing the nation with his new Nubian wife, having abandoned Zipporah back in Exodus 18:2. It get’s pretty ugly. There’s some yelling and some more smiting. And Miriam was struck with a disease, צָרַעַת, (and according to me in Daughters of Miriam and Rabbi Akiva in b. Shabbat 97a, Aaron as well). Miriam was banished to what I call “the camp beyond the camp” in my current work, the place where those who were טָמֵא waiting to be pronounced טָהוֹר stayed. The text says that the people did not move until the “gathering,” הֵאָסֵף, of Miryam. I like to imagine that the illuminating cloud got up to leave but the people would not follow without Miryam. Or perhaps God herself refused to move without her daughter. The family squabble was over. For now.

david30122013

May 25, 2013 5:09 pmIt is so refreshing and expanding to read of God in these non-male terms. I tried to make this same point to my congregation recently. This goes against the explicit teaching of most evangelicals I have heard, but behind that perspective is a desire to maintain the patriarchal status quo in the church. Keep shedding light on the path!

Wil

May 25, 2013 5:43 pmThank you. The irony is of course that many evangelicals claim to be literalists – except when the bible speaks of God in feminine terms.

Susan Burns

May 29, 2013 12:20 amWhat is your opinion of the meaning of the name Miryam?

Wil

May 29, 2013 9:08 amI’ve always used the simple, midrashic, “Bitter-Water-Woman” following Rabbi Lynne Gottlieb which presupposes two elements: מר – bitter and ים – sea.

Susan Burns

May 29, 2013 7:14 pmBut what do you think “bitter sea” could signify? “Sea” is already bitter so why the extra bitter?

Wil

May 29, 2013 7:20 pmIt’s a traditional, not philological reading; not designed to be exhaustive. Lexically, the name could be Egyptian. I don’t have a position.