Let us pray: In the name of God whose mercy is just and whose justice is merciful. Amen.

(Audio on multiple platforms available here.)

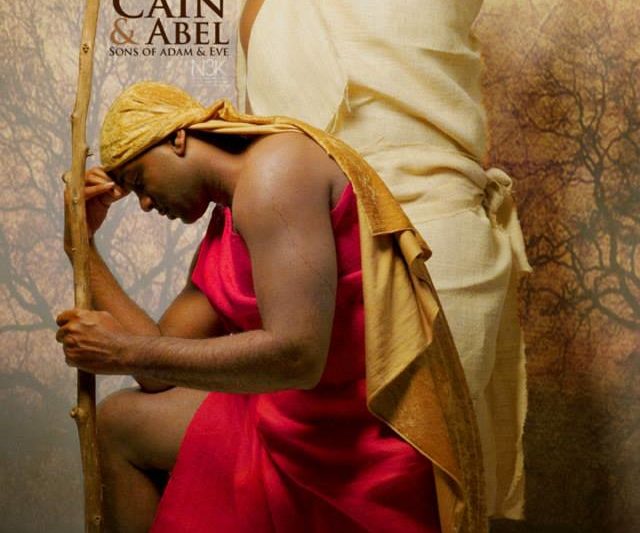

To be black in America is to bear the Mark of Cain, not because God turned Cain black for his sin as generations of racist biblical interpreters proclaimed, but because this white supremacist society has constructed an entire universe of evil, violence, incompetence, shiftlessness and promiscuity and equated it with blackness and Black people. There is a long history of reading Cain as black. There is an entire genre of artwork, in which Cain is portrayed as black or at least significantly darker than Abel, most of it coinciding with slavery and its immediate aftermath. In some of these portrayals Abel is as white as paper. Most importantly, Cain is black while he is killing his brother. In these visual exegeses the Mark of Cain is blackness from birth. Corrupt from the womb. And that is how America has seen and treated black folk.

In those readings, to be black was to be monstrous, violent, lethal. Those interpretations were the fruit of slaveholding Christianity which lingers far beyond the partially effective Emancipation Proclamation and the eventual eradication of plantation style enslavement in its original form or, in its successor forms–punitive poverty and mass incarceration, often on the those very same plantations. The demonization of blackness is at the heart of western Christianity and its rebellious American offspring. Monstrification is its contemporary form. Rodney King was super human. Mike Brown was a demon. George Floyd was large and dangerously out of control on drugs. Renisha McBride was shot before she could ask for help for her stalled out car because the homeowner was frightened of a black woman knocking on his door.

Black folk are the Cain of the American story in white supremacist biblical interpretation. White supremacists and nationalists in public office play God, marking some of us for death from birth. To be black in America is to be marked for death. Black folk are read preemptively as murderous Cain yet, with none of the forgiving rehabilitating grace God gave him, nor any of the value God put on Cain’s life. Like Cain, black folk have committed no crime by simply existing in the world that classifies our very blackness as the Mark of Cain. Even those racist readings that get the timing of the story right, that God marked Cain after his crime, missed the mark, if you will pardon the pun. The Mark of Cain isn’t punitive, it is protective. It is not the mark of death, it is the mark of life. In the story, God marks Cain to save his life. So if those white supremacist preachers and biblical scholars follow the logic of their own interpretive work insisting that blackness and dark skin is the Mark of Cain then, they would have to conclude that blackness is the gift of God, the mark of life.

But why even bother to imagine blackness for Cain in the first place? These early interpreters in all of our churches and denominations and the theological foundation for nondenominational congregations and independent churches were surely not affirming the historical and geographical truth that the ancient Israelites and their ancestors were Afro-Asiatic. Rather they start with their unexamined and unquestioned and absolutely wrongheaded assumption that the people on the pages of their Bibles were white like them. And then because they found themselves in a world in which their European kin who had begun the slave trade had now withdrawn from it and were beginning to say you can’t enslave a fellow Christian because they are your brother. That left them in quite the theological pickle because they had been using conversion as one of the excuses to justify slavery. So the oldest story in the scriptures about brothers and sibling rivalry was corrupted into a manipulative and mercenary theological support for continuing enslave their fellow human beings including those who were their sisters and brothers in baptism. This reading of scripture also had the advantage of stigmatizing black folk as perpetually violent from the womb and in need of civilizing through Christian practices like slavery after all, slavery is biblical. Let me remind you that everything biblical is not godly and is not for us to imitate or perpetuate.

Biblical interpretation can be quite a dirty business once all of the laundry is spread out for everyone to see. I start with this perverse and perverted reading of the Mark of Cain in order to make clear how much the fruit of this twisted theological tree is still being served up as apple pie in our American context. If you will allow me, I would like to clear the table of this poisonous dish and offer you something more life-giving and sustaining instead.

Journey with me, if you will, to the garden paradise of Eden, bordered by four rivers found in East and North Africa and, West Asia. Let us tell the story again.

To know how to hear a story requires knowing what kind of story it is. Too often folks get nervous at the thought of critical biblical scholarship because it might say that a beloved story is not true. Instead, in my teaching, I ask, “How is it true?” Some stories are ethically true. Some stories are historically true. Some stories are metaphorically true. Some stories truthfully reflect the culture, values and theology of those who wrote them down, preserved them, edited them and stitched them together in a library collection under the heading, “Words about God, Including Words from God and, Words through which God (Sometimes) Speaks (Sometimes).” It’s a long sign on a long shelf after all, the collection has more than eighty books. As an Episcopalian I am part of the majority tradition of Christianity which includes Catholics, Orthodox Christians and other Anglicans who have eighty books in our Bibles while our Ethiopian Orthodox kin have a few more. While Protestants, after chopping up the 80-book 1640 King James Bible in 1782, now have 66.

In those Words about God, our theological ancestors passed down to us a story of the inexplicable horror of murder. Like all the stories in the early cosmic, mythic, portions of Genesis, it is an etiology, a proposition for how it is that the things which are now came to be. One can almost imagine the story arising in response to an anguished grief-suffused question, “how could one human being do this to another?” The question is old. The question is timeless. The question is current. Once upon a time, a sage elder might have said, “It began as all stories do, with two people who did not set out to kill or be killed.”

Their story begins with their parents and the notification in Genesis 4:1 that their father had “known” their mother, the colloquial biblical Hebrew expression for sexual intimacy. The grammatical structure of biblical Hebrew doesn’t quite equate to our notions of verb tense so that knowing can be understood as they just had known each other intimately, or they had known each other intimately previously, in the course of their relationship. A relationship which is never called marriage in spite of the deliberate choice of some to translate the words “woman” and “man” in the story as “wife” and “husband” when those words don’t exist in Hebrew (or Greek). Rather, a woman is her man’s and a man is his woman’s. They belong to each other. That is what this first intimate partnership looks like when you peel back the layers of translation by folk whose motives we have learned to distrust. Perhaps we should stop trying to fit them into much later definitions and expectations of marriage, another word that is not in the text.

We don’t know when the woman and her man first knew each other intimately, sexually. Because sex is not shameful or sinful, there is no reason to imagine that they did not share and explore the beauty of their creation as fully sexual beings in their garden paradise. Indeed, traditional rabbinic scholarship teaches that Cain was conceived in the garden. The traditions that Eve and Adam did not have sex in the garden and therefore sex only occurs in the sinful world or, that having sex was the forbidden fruit that got them kicked out are largely Christian fundamentalist teachings steeped in shame about the human body and its sexual pleasures. Hyper-sexuality and promiscuity are traits white supremacy ascribes to Black folk and native folk and, in those white supremacist Christian fundamentalist interpretations, are the legacy of the Mark of Cain. Stigmatizing Cain’s conception marks him as bad from the womb in the same way that black folk were and are read as sexually deviant and violent from the womb.

Speaking for only the third time in the story that presents her life, Eve – Chava in her own language – utters a pun about the name of her son and her role in his production. It would be as though my mother had said “I have willed Wil into being.” Eve would have said something like, “I have crafted a craft.” And presaging Brittany, the next verse says, “she did it again,” without the “oops.” Mere words separate the births of the boys when biology would dictate two to five years of breastfeeding and a second nine month pregnancy intervened at the very least. It gets overlooked in English but there is an early sign that things will not go well for the second son. His name Abel, Hevel in Hebrew, suggests a fleeting existence or even a vain and frivolous one. It is the same word that the philosopher in Ecclesiastes uses to say that everything is vanity.

This first family of a new world order found their way in the world west of Eden without a manual. Cain followed in his daddy’s footsteps as a tiller of the soil and Abel forged a new path as shepherd and rancher. And without prompting or instruction, Cain brings some of his harvest as an offering to God. It is important to note what the text does not say as well as what it does. It does not say that there was anything wrong with his offering, that he brought leftover, rotten, spoiled or blighted produce. Those assumptions will be made later and read into the text, blaming him for something the text does not. Abel brought the fruits of his labor as an offering, following his big brother’s example and the text says it was the first fruits, meaning he did not know if the rest of the flock or cattle would get sick or die.

And God, in this story about how and why the world is the way it is, plays the part written as it is written, inexplicable and inscrutable. God who has never given instructions or made any expectations clear picks one side over the other. Rather asking if Cain was wrong for what he brought for his offering I ask, “How is this portrayal of God true?” Sometimes stories about sibling rivalry are really stories about unmerited favoritism. Sometimes favoritism is inexplicable. How could a nation that enslaves and exploits be allowed to grow to dominate all other nations? How could the stolen wages of stolen people on stolen land be converted into generations of wealth for those who committed those crimes against humanity and their descendants? At this moment in this passage God is much more like structural inequity, structural oppression rooted in questionable theology, than like a righteous judge, loving parent or redeemer of the wretched and ratchet. What is true about this passage is not that God is arbitrary or that Cain should’ve known better but, that we experience the world unequally and we don’t always know why it sometimes it seems as if God is not only not on our side, but seemingly rooting for the other team.

I started this sermon rejecting a white supremacist reading of Cain as black because the intent of that reading was to dehumanize black folk and justify our enslavement and violence against us and, we can see its legacy in the way black folk are policed today. This is not the only reading of the passage. We could also read black folk as Abel, marked for death and murdered by those who should have cared for us.

There are so many ways to read this text, to read any passage of scripture, that is part of its beauty. That is part of what it means to be a living and enduring Word. So, now I want to offer a Womanist reading of Cain as Black to explain how a people relegated to second class status and constrained by an inescapable set of strictures that stigmatizes them as inadequate, sometimes in the name of God, and denies them the benefits they see others enjoying through no distinguishable difference in their effort and labor, can turn to rage and lash out violently. What are you to do when the whole world as you know it and even God, as far as you can see and have been taught, is set against you?

Cain killed. Cain killed his brother. Cain killed his baby brother. Cain killed his Mama’s baby and his Daddy’s baby boy. His arms were too short to box with God and perhaps he didn’t know that he could argue with God. He had very few examples and the world in the story was so very young. He did what all hurt people do, he hurt someone else, someone over who he had some power, size and stature. I understand Cain like I understand my people’s pain. I understand the anatomy of a riot. I understand the explosion of black pain and rage and it gives me insight into the character of Cain. I know what it is to be marked for death. And I know what it is to be marked for life.

And while I do not recognize the God who disdains Cain’s gift as my God, I know the God who marks him very well. I recognize the theology that says says to transgress as Cain transgressed is to be cursed for all time, to wear the label felon around your neck no matter what you do subsequently. But I also know that is not the end of the story with God. All the world has written Cain off as a fratricide, a man – or boy – who killed his own brother. How does the story change if Cain is a an angry sullen hormone filled teenage boy? Will we throw him away forever? Doesn’t he deserve a second chance? God thinks so. Yet, if he were a black boy, he’d be more likely to be arrested, more likely to be convicted, more likely to be denied bail, more likely to be convicted and more likely to be sentenced longer than a white boy who committed the same crime. Boy or man, the Church has thrown away Cain. No one but God is interested in the redemption or rehabilitation of Cain.

God marked Cain with her own sign. What the world, and even Cain thought was the mark of death was the mark of life. God marked Cain so that he would live. God marked Cain so that he would survive and thrive. There was a world to be peopled. Now the story will jump the shark here because Cain will marry and there are no other people identified in the world and, he believes that people who see him will kill him because of what he has done. It is for those other people that God gives Cain the mark. Some folk will go to great lengths to explain canes marriage and all of those other people and invent sisters and incestuous unions out of their theologically impoverished imaginations, but I believe the God of Genesis who created the whole world with mere words is more creative than that. I also believe not all mysteries have to be explained. And the purpose of this story is not to fill the holes in all of the other stories just as it is not a historical or scientific accounting of the world and its peoples.

God marked Cain. God marked Cain for life. But some can only see him as marked for death. Some will never let go of his past. But God is the God of redemption and rehabilitation and new life and new possibilities. And this is how redemption works, it is not just for Cain. Redeeming and rehabilitating Cain in the story means that we must hold out the possibility of redemption and rehabilitation for those who stigmatized Cain and black folk in his name. White supremacy cannot be redeemed. But folk who perpetuate and benefit from white supremacy, which is every bit as lethal as Cain’s murderous rage, can be redeemed. No one is beyond the redemptive grace and love of God. But first, Cain put down his rock and he never picked it up again. When white supremacist fists put down their rocks, and sometimes guns and badges, we can talk about redemption and rehabilitation.

Our ancestors left us this story so we could makes sense of the things in our world that they struggled to understand in theirs. When we read it in new ways, we are doing the work they left for us to do.

Our ancestors also left us this story as a testimony to their God, our God, my God. God didn’t throw away Cain. God didn’t even take his life. God created space for him to live into who he could be while living with who he was, and the world is the better for it. There are folk I want to throw away. There are folk through whom I can’t imagine–even within the realm of my sanctified imagination–that there will ever be any worthwhile contribution to our world from them or their spawn. Their hands are every bit as bloody as Cain’s. But I believe in a God whose mercy is just and whose justice is merciful. The God who heard Abel’s blood cry from the earth is also the God who kept Cain. The God who cares for Cain is the God who demands justice for Abel. God’s justice is as inescapable as God’s mercy, is as inescapable as God, God with us, God with even Cain.

That same God became a child, begotten, birthed, breastfed, bathed, baptized, and buried. God came to us in our own failing and fragile human flesh. In living, in loving, in healing, in teaching, in dying, in rising, God in Jesus is the God who will not abandon us to our circumstances, our choices, or their consequences. We are Cain and and we are Abel, marked for death and marked for life. Amen.

Genesis 4:1 Now the human had known his woman Chava, Eve, and she conceived and gave birth to Qayin, Cain, saying, “I have crafted a person with the Creator of Heaven and Earth.” 2 Then she went again to give birth, to his brother Hevel, (Abel). Now Hevel was a shepherd of the flock, and Qayin a cultivator of the ground. 3 And it was after some days Qayin brought to Earth’s Creator an offering of the fruit of the ground, 4 and Hevel brought some of the firstborn ewes of his flock, and their fat portions. And the God Who Chooses had regard for Hevel and his offering, 5 but for Qayin and his offering the Inscrutable God had no regard. So Qayin was very angry, and his face fell. 6 The God Who Attends said to Qayin, “Why are you angry, and why has your face fallen? 7 If you do well, will it not ascend? And if you do not do well, at the opening sin reclines; its desire directed towards you, but you will master it.”

8 Then Qayin said something to his brother Hevel; now they had gone into the field. And when they were in the field Qayin rose up against his brother Hevel and killed him. 9 Then the God of All Flesh said to Qayin, “Where is your brother Hevel?” He said, “I don’t know; am I my brother’s keeper?” 10 Then the Just God asked, “What have you done? A voice…your brother’s blood-spills are crying out to me from the ground! 11 And now cursed are you from the ground, which has opened her mouth to receive your brother’s blood-spills from your hand. 12 Therefore, when you cultivate the earth, she will no longer yield to you her strength; you will be one who wanders and staggers throughout the earth.” 13 Qayin said to the Gracious God, “My punishment is greater than I can bear! 14 Look! Today you have driven me away from the soil on the face of the earth, and I shall be hidden from your face; I shall be one who wanders and staggers throughout the earth, and anyone who meets me will kill me.” 15 Then the God Who Hears said to him, “It shall not be so! Upon anyone who kills Qayin there will be sevenfold vengeance.” And the God Who Watches put a mark on Qayin, so that no one who came upon him would kill him. 16 Then Qayin went out from the presence of the God Who Saves, and settled in the land of Wandering called Nod, east of Eden.

Megan

June 21, 2021 9:48 pmGod led me to your article through the beautiful photographs! I am currently reading through Genesis. Your points are so well laid out. Your linguistic style is so thought evoking! It truly brought tears to my eyes. I fully added “theologically impoverished” to my vocabulary! Such an apt description of so many “Christians” How people can read the same Bible and find anything in it that would lead them to believe that God is anything other than Love is beyond me. Thank you for your time and thoughts! I am so grateful to know that we will be in heaven together! God Bless you and your ministry!

Yours in faith,

Megan

Rufus Mosley

September 5, 2022 6:30 amBeautiful and thought provoking. Thank you