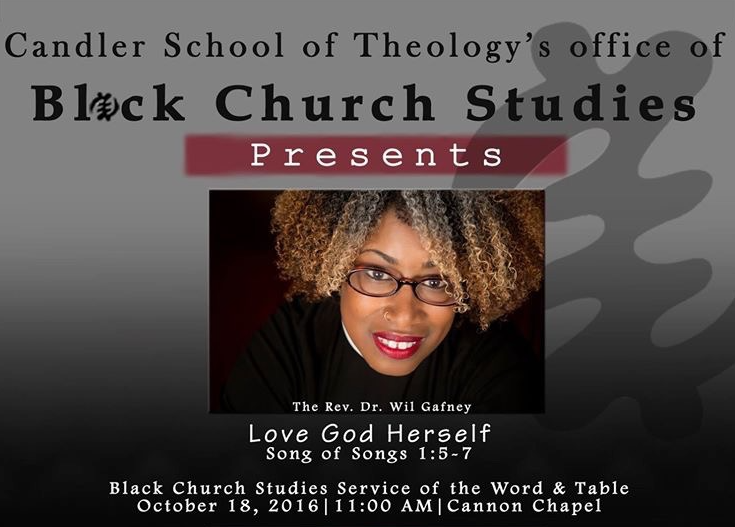

2016_10_20 Wil Gafney from Candler School of Theology on Vimeo.

Yes, I am black! and radiant–

O city women watching me–

As black as Kedar’s goathair tents

Or Solomon’s fine tapestries.

Will you disrobe me with your stares?

The eyes of many morning suns

Have pierced my skin, and now I shine

Black as the light before the dawn.

And I have faced the angry glare

Of others, even my mother’s sons

Who sent me out to watch their vines

While I neglected all my own.[1]

Normally I only preach from my translation of the scriptures believing you can’t preach what you don’t read, and reading the bible in English is like eating when you’ve lost your sense of smell. Rabbi Marcia Falk’s translation of the Most Excellent of Songs, the Song of Songs, is itself most excellent so I invite you to consider for the time that is ours the following lines:

The eyes of many morning suns

Have pierced my skin, and now I shine

Black as the light before the dawn.

And I have faced the angry glare

Of others, even my mother’s sons

Who sent me out to watch their vines

While I neglected all my own.

Black is beautiful. Not just some black is beautiful. Not just that light, bright, almost white, mixed with something, Becky with the good hair, Beyoncé, video girl type A or B (but not so much C or D) black is beautiful. My black is beautiful. Your black is beautiful.

Whether hailed as luminous darkness or radiant blackness, our black is beautiful. Hand-crafted sun-kissed shades from cream to coffee—no sugar, no cream—to blacker than a thousand midnights to the bluest black, from the bluest eye to the grey, green, brown, black eyes deeper than the well of souls, crowned with cottony soft puffed crowns, regal ropes, intricate braids, coifs and cuts in every color imaginable and some you couldn’t, or smooth shaved like Luke Cage. All of these studies in black are beautiful. Black is beautiful. Blackness is beauty. Blackness is worshipful. All blackness is divine. It is the imprint of the holy darkly radiant God in whose image we are created. Look in the mirror and love God herself in you, in your fam, in your heart and skin kin, in your neighbors and strangers, enemies and allies.

The eyes of many morning suns

Have pierced my skin, and now I shine

Black as the light before the dawn.

In the black church we trumpet our love for our blackness—Imma come back to that—but we don’t always love our black bodies. The black church loved us and taught us to love ourselves when nobody else would and folk were out here in these streets hating our skin, our hair, our lips, our noses, our thighs, our buttocks, our thickness, our swish, our sway. And at the same time some in the black church were separating us like goats from sheep based on brown paper bags and talking about good hair. Perhaps even more insidious, too many black churches still privilege whiteness in theology and culture, expectations about dress and deportment, trying to please an abusive white supremacist culture that does not love us and despises our flesh.

The whiteness against which we have been defined, measured and found lacking has been deified and is hanging on the wall in too many churches and homes. The white-Christ-idol hanging on the wall denies the bruised black beauty of God in human flesh killed by the uniformed arm of the empire like too many of our trans and cis sisters and sons. Be very clear, white Jesus is does not love you and cannot save you; he is the god of white supremacy and the demonization of blackness is its gospel.

But…

The eyes of many morning suns

Have pierced my skin, and now I shine

Black as the light before the dawn.

This beautiful blackness is the gift of God. It is delicate and diamond strong, fragile and fearless, resilient and resplendent. Our blackness is more than the skin we’re in, it is the treble of our souls, the multi-strand web of our culture that binds us to all our folk—and the rest of God’s folk too, for we are all children of the same mother, from the African earthen womb of the God who writhed in labor with us and Rock who gave us birth. (Deut 32:18) And like all of God’s good creation we are charged with its care, care for ourselves, our bodies, our minds, our souls, the sacred trust of our blackness.

I believe that we ought to be passionately in love with ourselves, our bodies and our blackness. For this I take my lesson from the Song of Songs which has scandalized so many Jewish and Christian interpreters because it does not talk about God explicitly, instead it focuses on the love of two people expressed sensuously, sexually. It is all about the love of and between two black bodies—offered as scripture and revelation. Now, one of those bodies is blacker than your average brown-to-black ancient Afro-Asiatic person. She is black as a black-haired goat. Y’all can have them white cotton ball sheep, I’m going to hang out with the goats. Let me let her tell you about herself as we walk through this text together:

shechorah ani v’ navah

I am black…

Actually, it’s the other way around. Black am I… Black is the first word. Blackness a priori. Black before all else, intentionally, by design, according to the will (and the Wil) of God for my life. Black am I…

Black am I and resplendent.

Black am I and radiant.

Black am I and exquisite.

Black am I and beautiful.

It seems the city-women can’t keep their eyes off of her. They keep staring, looking her up and down. And you know how we do; she asks them if they like what they see:

Will you disrobe me with your stares?

The shout out to the daughters of Jerusalem is an acknowledgement that our bodies are always under scrutiny. We are weighed and measured, consumed and labeled acceptable or defective in a glance. The black beauty Shahorah—we can call her Ebony, Raven, Jet or Onyx—Shahorah says you call me black like that’s an insult. Let me tell you, I am black, as silky-black as the luxurious coat of a Kedari goat, like mink, only blacker. I see you looking, you can’t keep your eyes off of all this good black. And neither can the sun.

The eyes of many morning suns

Have pierced my skin, and now I shine

Black as the light before the dawn.

She says, don’t stare at me because my beautiful black skin has gotten even darker while I bask in the sun. Our black beauty revels in the blackness of her skin and has the nerve to get a tan on top—we hadn’t destroyed the ozone layer yet so she didn’t have to worry about melanoma—she embraces the kiss of the sun and some folk are out here bleaching their black.

And I have faced the angry glare

Of others, even my mother’s sons

Who sent me out to watch their vines

While I neglected all my own.

The angry glare is a reminder that everyone won’t look at us and see the glory that God created. Some folk are mad that we’re still here. Mad that we haven’t been destroyed. Mad that we survived the hells of the middle passage, slavery, Jim Crow and lynch law. Mad that we have the right to vote. Mad we’re exercising our right to vote. Mad that it looks like we’re benefitting from affirmative action when it benefits more white women than black women or men. Mad we’re in their schools and on their jobs. Mad some of us are in charge of some of them. Mad this continent once peopled by red and brown peoples is turning brown again. Mad we don’t back down, step aside, shuffle when we’re not dancing and scratch when we’re not itching. There are some angry folk out there and you can see it in their eyes long before they open their mouths or send the first tweet.

And I have faced the angry glare

Of others, even my mother’s sons

Sometime the angry glare is more than a look. Sometimes it’s a catcall. Sometimes it’s a death sentence executed in the street because you refused to acknowledge a cat call, smile, or give out your phone number. Our blackness is under assault, verbal assault and even physical assault. Sexual harassment and predation is a matter for the church because it happens in church to church folk and is perpetrated by church folk.

We can’t talk about taking care of black bodies in or out of the Black Church without talking about the perils black women and girls face from black men and sometimes boys in and out of the church, and in and out of the pulpit. That peril is often physical and sexual violence as Shahorah knows first hand. She tells the story of her sexual assault in 5:7:

The men who roam the streets,

guarding the walls,

beat me and tear away my robe.

Don’t miss that the men who assault Shahorah are the men who guard the walls. If we read them religiously they are the men responsible for maintaining order in the city where God dwells. If we read them civilly they are the men responsible for protecting the city and her citizens from those who would prey upon her. Pastors and police can be equally dangerous to black girl magic.

And I have faced the angry glare

Of others, even my mother’s sons

Later in the text (8:8-9), Shahorah describes the efforts of her own brothers to constrain and confine her, to make her conform to their notions of comportment.

We have a young sister

Whose breasts are but flowers.

What shall we do

When the time comes for suitors?

If she’s a wall

We’ll build turrets of silver,

But if she’s a door

We will plank her with cedar.

Being unapologetically black out loud and in public sometimes means scrutiny and censure from your own people who still believe that respectability politics will save them, and all too often what is respectable, civilized, decent and professional is what white supremacist culture demands. Like so many good church women Shahorah’s self-care has been side-tracked while she takes care of everybody but herself.

And I have faced the angry glare

Of others, even my mother’s sons

Who sent me out to watch their vines

While I neglected all my own.

It’s time to tend our own vines and their sweet, luscious, intoxicating fruit. It’s well past time for us to love God herself in ourselves and each other. Too long the church has taught us to love others at the expense of ourselves. It doesn’t work that way boo. As Rev. RuPaul asks, How the hell you going to love somebody else if you don’t love yourself? Can I get an amen up in here? The answer is you can’t. You cannot love anyone else—or tell them how and where to love you, how exactly it is you like to be loved—if you do not love yourself, all of yourself, in every way.

But some of us don’t love ourselves. We have been told for so long that our blackness is bestial, fit only for the end of a rope. Our despised bodies were raped and plundered by those who hated us, literally hating on us with their unwanted bodies. Their descendants plunder the creative riches of our culture all the while denying we have a culture, compounding the theft of our labor while relegating us to under-resourced schools and neighborhoods, all the while pathologizing our beautiful blackness when they’re not hunting us down in city street safaris. They work so hard to cast our blackness as the demonic so they won’t have to accept the fact that they have been killing God herself. All the while appropriating our hairstyles and recreating our contours.

It is no wonder some children looking at the world unfolding around them don’t want to be black and can’t see the gift it truly is. Some of us can’t help our children find the holiness in God’s touch on their skin because we have been so brutalized in and because of our skin, hair, diction and mannerisms we wish we could be somebody else too. It can be hard to love yourself, no matter how woke you are, when you are bombarded with so much hate for your person and your people, passed down as an intergenerational curse millennia after millennia. Isn’t any wonder so many of our bodies, minds and souls are unhealthy? You can’t care for your black body if you don’t love your black body.

It’s time to tend our vines. It’s time to tend our own vines. It’s time to tend the vines of our minds. It’s time to tend the vines of our souls. It’s time to tend the vines of our beautiful black bodies. It is time to love ourselves and love on ourselves. It is time to be our own best lover. It is time to know every inch of our flesh, revel and delight in it: every curve, every roll, every wrinkle, every freckle. How are we going to know when something feels wrong in our breasts or testes when we don’t know what they feel like when nothing is wrong?

What happens to your vine is a community affair. Our vines are all planted in the same vineyard. What happens to your vine affects my vine and what happens to my vine affects your vine. What we do or fail to do in the care and nurture of our vines is not just confined to our own bodies. In our strength we can strengthen others. A strong vine can help support a weaker vine. But a diseased vine can infect the whole vineyard.

When you hurt me, you hurt yourself

Don’t hurt yourself

When you diss me, you diss yourself

Don’t hurt yourself

When you hurt me, you hurt yourself

Don’t hurt yourself, don’t hurt yourself

When you love me, you love yourself

Love God herself [2]

[1] Translation of Song of Songs Poem 2 (1:5-6) by Rabbi Marcia Falk (The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2004.

[2] “Don’t Hurt Yourself,” Beyoncé, Lemonade, Parkwood Entertainment/Columbia Records, 2016.

Vivian

October 19, 2016 7:27 amWell done Wil.

Jennifer Dawson

October 19, 2016 8:41 amBeautiful

Ginger Tansil

December 6, 2016 4:28 pmWow!