Love. Sex. Money. Power. Death. All of these things are present in and behind our lessons, particularly the first two, especially if you know where to look. Let us look with eyes wide open at the treasure house of the scriptures and see what they have to say to us across the expanse of time, that we might find a living word from the Living God in these words we share today. Let us pray:

Love. Sex. Money. Power. Death. All of these things are present in and behind our lessons, particularly the first two, especially if you know where to look. Let us look with eyes wide open at the treasure house of the scriptures and see what they have to say to us across the expanse of time, that we might find a living word from the Living God in these words we share today. Let us pray:

Holy One of Old, open our eyes that we may see and our ears that we may hear. Amen.

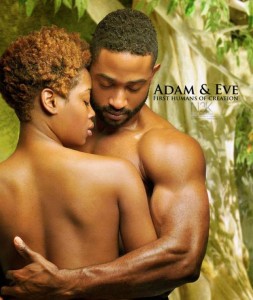

[Adam and Eve by James Lewis; Song of Solomon by He Qi] Today’s lesson from the Song (2:8-13) is part of a larger work celebrates human sexuality as part of God’s good creation. In the Song, the woman and man are in harmony with one another and with the natural world; the brokenness of relationships between humans and, between humans and the earth is healed, (Phyllis Trible in God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality). The garden in the Song is a sustaining oasis nourishing its human, plant and animal occupants. The woman and man are in what some have described as an egalitarian, non-hierarchical relationship. That may be too generous but it is clear the relationship between the woman in the Song and her man is unlike any other in the scriptures. Yet the world of the Song is not paradise; there are threats: There is some degree of societal and familial disapproval of their love demonstrated by the attempts of some men to regulate the woman’s sexual expression, (5:7; 8:8-9). The bible is, after all, an Iron Age text.

Today’s lesson from the Song (2:8-13) is part of a larger work celebrates human sexuality as part of God’s good creation. In the Song, the woman and man are in harmony with one another and with the natural world; the brokenness of relationships between humans and, between humans and the earth is healed, (Phyllis Trible in God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality). The garden in the Song is a sustaining oasis nourishing its human, plant and animal occupants. The woman and man are in what some have described as an egalitarian, non-hierarchical relationship. That may be too generous but it is clear the relationship between the woman in the Song and her man is unlike any other in the scriptures. Yet the world of the Song is not paradise; there are threats: There is some degree of societal and familial disapproval of their love demonstrated by the attempts of some men to regulate the woman’s sexual expression, (5:7; 8:8-9). The bible is, after all, an Iron Age text.

In our lesson this Sunday the lovers articulate their love for each other’s flesh. This text is a lovely reminder that our physical bodies are beautiful and beloved, and that loving relationships occur within and not in spite of human bodies. [tweet that] The lectionary portion begins with the woman extolling the way the man moves in v 8. Then she exclaims over the way he stands still and looks out the window in v 9; she is besotted with every little thing he does. She repeats some of his words to her – it is unclear when he first spoke them. (There is little underlying narrative or chronological order in the Song.) The man asks his love to run away with him; they aren’t running away from anything or towards anything. They just want to be together in a world as beautiful as their love. The natural beauty of the world around them reflects their love, blossoming flowers, fruit-laden trees, singing birds. Maybe it is paradise, or the Garden Isle of Kauai.

The natural world evokes all of the senses as does the love between the couple. The very physicality of this text as scripture is its gift. The woman, man, their love and their world are all God’s good, very good, creation. There is no division between body and soul. The Greek philosophical tradition that will become so important to the Church Fathers as many of them reject and restrict sensuality, sexual love and bodiliness is unknown here. This text does not share the later dualism separating flesh and spirit inspired by Greek philosophy in which the body and its desires are regarded as being lower or lesser than spiritual things. Body and soul are one here, united in love.

[tweet this] The Song of Songs is a celebration of erotic love, by which I mean explicitly sex. Not surprisingly its literal reading was quickly abandoned in favor of allegorical readings in much of Judaism and Christianity where it has been read as symbolizing the love of God or Christ for Israel or the Church. No small feat given that neither Christ nor Israel, nor even God are mentioned in the Song. It’s about sex and love and death to some small degree. [tweet this] We dare to love though we die. We risk death because we love. Love and sex, sex and death have been intertwined since the first stories in that other garden where love went wrong and started looking like the heteropatriarchy because of a curse. [tweet that]But here in this garden there is love and some degree of equanimity in spite of the old curse. Here a woman dares to tell the world about her love, her desire, her sexual desire, her intent to fulfill it without shame. She does so in the only biblical book in which a woman is the dominant character and speaks the majority of the lines. The Song of Songs is unique in the scriptures for its passionate lyrics extolling the physical love between a woman and a man, and for the dominance of the woman – in voice and agency – in the composition. It is a marvel – perhaps a miracle, an intentional act of God defying the previous order of things – that the Song was received as scripture. It was resisted and rejected by men before it was grudgingly accepted.

[tweet this] A literal reading of the Song requires coming to terms with the raw sexual desire and gratification called for by this woman to her man in the scriptures which many readers found – and find – incompatible with their notion of scripture in spite of the fact that these verses are enshrined and canonized. In many readings that do celebrate the sexual love between the couple, their marriage is asserted in spite of the fact that the text does not state that they are married. The man does refer to the woman as his bride (Song 4:8–12; 5:1) and sometimes as his sister (Song 4:9–10, 12; 5:1–2; 8:8) though no one seems to want to take that literally – it is not clear whether they are betrothed or married, and if they are married why she spends so much time looking for him or they feel the need to sneak around. All that sex talk, conveniently excised from today’s lesson which ends as they run away together, inconveniently ending before the most luscious descriptions of their love-making.

And then for some reason the lectionary shapers gave us an equally truncated piece of Ps 45. Perhaps they reached into their grab bag of bible verses and it was on top. It too is about love. But not the kind of love in the Song. I’m a Black Church Episcopalian so I need you talk back to me. To whom is the Psalm written? I love the NRSV translation of v 1 – not something I say often:

My heart overflows with a goodly theme;

I address my verses to the king…

So, to whom is the Psalm written? If we just read that verse, we might say, “Well, God is often described as a king (in spite of not actually being male).” But look at v 2:

You are the most handsome of men…

therefore God has blessed you forever…

This is a psalm about a human king. Is there any love here? Does the psalmist love the king? Or does he love his wealth and power? It sure seems like the psalmist has some kind of love for him. [tweet this] When was the last time you read a psalm praising someone other than God? You can find the whole psalm on p 647 in the prayerbook – I have little love for that translation. Take a quick look at the love of the psalmist for the king: v 3 his thighs and his might, v 4 truth, justice and the Israelite way, v 5 his hands and his strength. In v 7 I think editor of the psalter said we have to have something about God in here so we get a one liner about God’s throne then back to the man of the hour. He’s better than all the other dude-bro-kings, his clothes and cologne are better, his women and their bling are better and look! a wedding at the end of the psalm. But there is no love there; this is a political wedding. This is the wedding of Jezebel to Ahab; her titles, “daughter of Tyre” and “king’s daughter,” are present in the text, rendered “people of Tyre” – a deliberate mistranslation – and “princess.” Jezebel is the only Tyrian princess to marry an Israelite king; the psalmist addresses her directly. In v 10 the psalmist tells her to forget the people and the place she loves. He does not believe that she can love her new people and her own people. The psalmist’s notion of love is very different from the lovers’ understanding. It is much smaller.

In the Song there is more than enough love to go around. It is practically sprouting out of the earth like flowers. In the psalm, all love and loyalty go to the king. Even God gets short-changed in the psalmist’s praise. We ought not be surprised. [tweet this] When love and sex intersect with money and power, love often seems constrained and reduced to shadow of itself.

James (1:17-27) offers another vision of love, love beyond that of lovers for each other. One of the songs of my people asks, “Have you got good religion?” The response: “Certainly, certainly, certainly Lord.” What is the evidence? The second verse asks, “Do you love everybody?” “Certainly, certainly, certainly Lord.” Perhaps today’s lesson from James was the inspiration. He teaches that what we say and what we do matters. We cannot say we love God, have good religion – or any religion at all – and say anything to anybody. This is an election season Gospel: one measure of your religion is what you say, including about candidates. And, [tweet this] we cannot say we love God and have good religion and not care for God’s children, widows and orphans yes, and the homeless, hungry, uninsured and under-insured, imprisoned – rightly or wrongly – diseased and afflicted, trafficked, migrants with and without papers, the hurting and even the hateful. I love that James doesn’t limit “religion” to Christianity. We are not alone in doing the work of God’s love in the world.

The Song teaches us to love with abandon. The Psalm shows us how wealth and power can warp love. The Epistle reminds us that love extends far beyond us, that it is not something we feel but something we do.

And Jesus, Jesus who is love seems to be talking about anything but. It seems the lesson of the Song has been forgotten. Folk are worried about controlling the body; all that flesh and its potential for pleasure makes a lot of religious folk uncomfortable – and not just in the Iron Age. And [tweet this] Jesus makes what I think is an overlooked point (in Mark 7:15): The body is not evil nor the source of evil. He says: there is nothing outside a person that by going in can defile, but the things that come out are what defile.

Yes, Jesus just made a poop joke. But more than that, by focusing on what folk say and do with their bodies and not their bodies themselves, Jesus aligns himself with our lovers. That ought not surprise us because Jesus overcame his culture’s aversion to Gentile flesh and never seemed to share their aversion to woman flesh. [tweet that] Jesus also offered his flesh to touch and be touched by folk whose flesh was said to be polluted and polluting.

After all Jesus is the one who emerged into the world in scandalous flesh, clothed in the flesh and bathed in the blood of an unmarried woman with a damaged sexual reputation. Jesus entered the world between a woman’s thighs uncomfortably close to urine and feces – not just in the stable but also in that most intimate female space. And perhaps most scandalous of all, Jesus did this as God, taking on human flesh, joyful, loving, touching, sexually maturing and capable flesh. In Jesus, God is all kinds love and, all of our love, which comes from God, is worthy of God and therefore an extension of God’s love. [tweet this] We are the beloved of God, with and in these bodies and their loves, not in spite of them.

In the Name of God who is Love, Jesus the Love that is stronger than death and the Holy Spirit who covers us and fills us with her Love. Amen.

Charles

August 30, 2015 6:21 pmWil this was a #Fabbylous read thanks for the great insight.

Pc

Arnold Jenkins

September 12, 2015 2:23 pmI appreciate your insights and generally do agree with you, however I would make a point to not ignore that there can be no limiting of God. This also means that relegating a narrative or text in the Bible to one meaning usually leads to mis-translation. I find most texts in the Bible unless otherwise stated are layered as our God has unknowable depths. And I would also add that I find every woman in the Bible to be a leader. At least those who were used for His purposes. Thats a whole nother article though. Anyway thank you for sharing and all the best.

Debasis Bhowmik

February 4, 2023 9:15 pmVery good