Tisha B’Av, the ninth day of the month of Av, on the Jewish calendar marks a series of sorrows, most notably the multiple destructions of the temple in Jerusalem. It has always struck me as impoverishing that Christians neglect the story of the fall in the lectionary and in non-lectionary preaching as my students over the years have confirmed.

The fall of the temple is so important in and for the Hebrew Scriptures that I begin my introductory courses there:

The destruction of the temple by Nebuchadnezzar was theologically incomprehensible. Nebuchadnezzar’s assault was as unimaginable as – not the events that we remember from September 11th, for the towers had been struck previously – but rather as unimaginable as the assault on Pearl Harbor, and, as incomprehensible as the bombs we dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and as unfathomable as was Japan’s ultimate surrender to her own citizens.

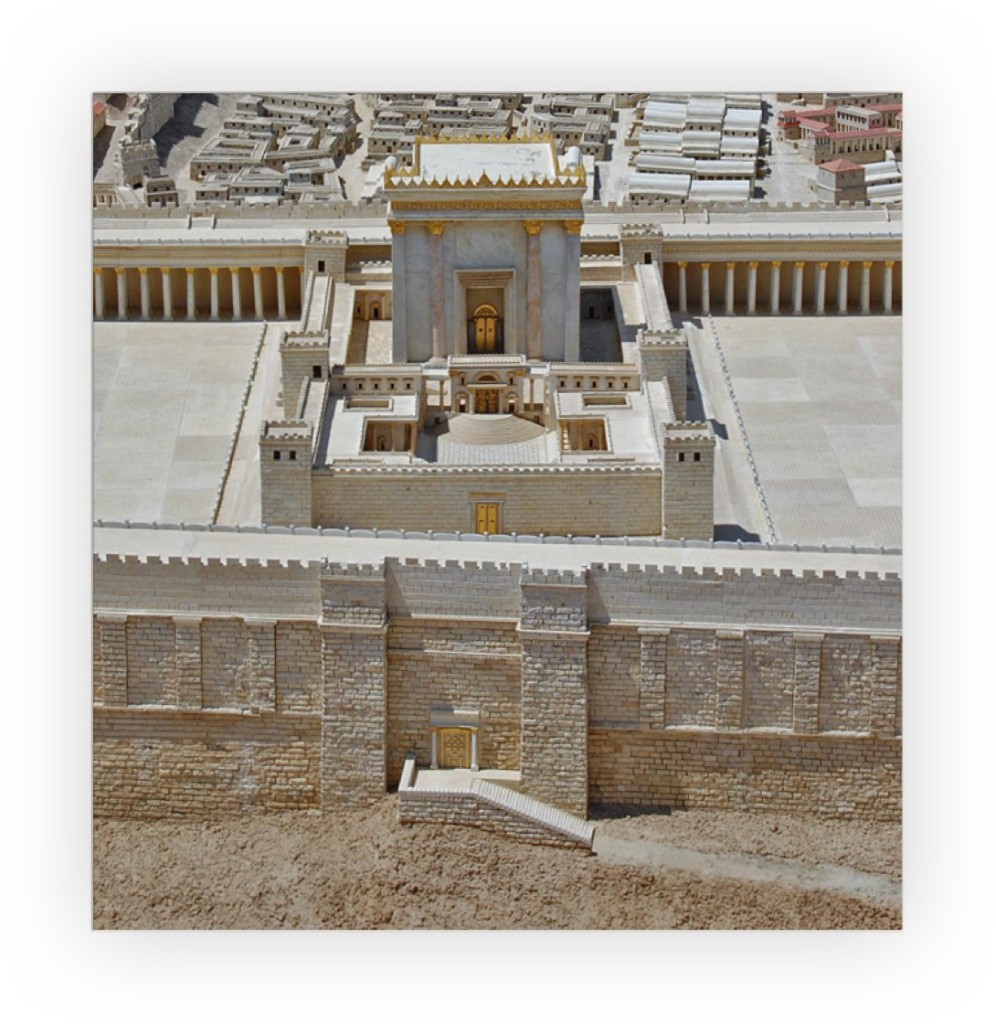

There was a time when no one could enter the most holy space in the temple except the high priest, and then only once a year. Tradition says that he wore bells so that people would know if he was able to survive in the presence of God and, that he had a rope around him so that if he dropped dead from proximity to the holiness of God, his mortal remains could be pulled out for burial.

And yet, Nebuchadnezzar’s troops not only entered the most holy place, they butchered it with battle axes, hatchets and hammers, chopping it to bits, burning everything that would burn, melting down the gold and silver and bronze for the Babylonian treasury. And they took a few choice vessels, used to worship the God of Israel back to Babylon for the king and his court to toy with.

And there was not even a puff of smoke. There was no strike of holy lightening; no burst of fire from heaven, no hailstones, plagues of Egypt, earthquake or sinkhole; the earth did not swallow them whole. Nothing happened. It was almost as if the temple was empty.

It must have seemed like the stories of Miriam and Moses and the promises God made to their descendents either never happened or were null and void. It may have seemed like the stories of Exodus were irrelevant fairy tales. Imagine, if you can, what it would have been like if the assault on and collapse of the Twin Towers was followed by an assault on and collapse of our government, defeat of our military and forced exile of our citizens: no homes, no jobs, no healthcare, parents separated from children, dead bodies heaped in the streets, everyone subject to robbery, rape – if not murder – on the way to incarceration in an over populated refugee camp with out any social services.

The scriptures of Israel were written in response to the occupation of its smallest surviving enclave by the Babylonians and recorded from oral traditions passed down from one generation to another. In the face of the overwhelming power of the Babylonian military which they touted as proof that their gods were more powerful than Israel’s lone god, in the face of their liturgy and pageantry and against the back-drop of Babylonian scripture, some Israelites were tempted and swayed to adopt Babylonian culture and religion. Others began collecting their own stories of who they were and who is their God.

The only response to such sorrow is lamentation. Indeed the book of Lamentations is the liturgical reading for Tisha B’Av. Christians in the African diaspora also know the power of lament. The most poignant laments I know come from African American spirituals. Sadly, in this world, the songs of lament will never be silenced.

Annie

August 1, 2017 8:08 amThank you for this enlightening article. I wish I had you as a professor.

SrAnnie