Gen 12:1 Now the Holy One said to Avram, “Get-you-gone from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great. Now, be a blessing! 3 I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and they shall be blessed in you, all the families of the earth.” 4 So Avram went, as the Holy One had told him; and Lot went with him. Avram was seventy-five years old in his exodus from Haran. (Translation, Wil Gafney)

Gen 12:1 Now the Holy One said to Avram, “Get-you-gone from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great. Now, be a blessing! 3 I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and they shall be blessed in you, all the families of the earth.” 4 So Avram went, as the Holy One had told him; and Lot went with him. Avram was seventy-five years old in his exodus from Haran. (Translation, Wil Gafney)

Let us pray:

May my teaching pour like the rain, my word go forth like the dew; like rains on grass, like showers on new growth. Amen.

I am deeply appreciative of the opportunity to share my teaching with you this weekend, and my preaching today, thinking about how to decenter whiteness, patriarchy and heteronormativity from biblical interpretation. And as a joke or perhaps as a challenge, you have invited me on a day in which the lectionary begins the story Abraham who will become the patriarch without peer, with patriarchy itself portrayed as God’s gift and blessing. And as much as I like the hashtags #smashtheatriarchy and #burnitalldown, peeling back layers of patriarchy and heteronormativity from the biblical text requires a somewhat softer touch if one seeks to preserve and peruse the text for a living word.

I could just preach from another text. For rejecting the constraints of the lectionary with its own patriarchal and androcentric agenda is most certainly a legitimate strategy to decenter that which has taken up entirely too much space in the biblical imagination and those of its interpreters. Even so I believe that any text, including the very epitome of a patriarchal text, can be preached as a relevant living word free from those encumbrances that keep us from living fully into God’s image and creation of us.

And still, patriarchy, androcentrism, misogyny, heterosexism, xenophobia and whiteness are hard to disentangle from the biblical text and its interpretation. They are sticky and clingy. Yet I believe that if we wrestle with this text we will find a living word from these sacred but troubling stories, one that is as true for Hagar, Sarah, Keturah and Lot’s daughters as it is for Abraham and Lot.

Wrestling a life-giving word out patriarchal and heteronormative constraints in the text and whiteness spackled on in interpretation of it is a labor of love and a life giving and saving enterprise. All too often the text confronts me with a god I recognize but do not serve, love or even want to know. There are texts of terror in both testaments. There are rapes and rape-based metaphors, slavery and slave-based imagery, canonized and sanctified, even placed on the lips of God, incorporeal and incarnate in the person of Jesus. And, as we who studied together yesterday have seen, the text is then often whitewashed in interpretation, particularly cultural, iconic and artistic interpretation, with no better image of whiteness sanctified than the idol that is white jesus.

The God who dwelt among us as mortal-immortal human yet divine Afro-Asiatic Palestinian Jew is present in a biblical text that is itself both human and divine, intricately interwoven. God is in the text and God is behind the text and beyond the text, in the characters the authors and editors hold up for us, and in the ones they neglect and turn away from, in the Canaanites and Moabites, in the trafficked and enslaved, in the women and the children, in the gentiles and foreigners, in the conquered and the subjugated.

[I am a black woman who knows she is made in the image of God and sees the divine in myself and my people, and in all of the other despised peoples of the earth. I see the holy and living God in the faces of neighbors and strangers, transgender and non-binary, genderqueer and cisgender, same gender loving and bisexual, heterosexual, coupled, parenting or child free, every shade of black, brown, beige, tan, pink, peach and cream.]In these stories about Abraham and Lot, the psalmist and her God, Jesus, Nicodemus, and the Mother of All from whom we must be born again, I see the God of my ancestors, the God of my faith, the God of my experience and the God of Jesus, the Son of Woman. I find her in these texts when I sit with the characters on the margins, those who have been cut out of the lectionary, and those whose names have been erased from the scriptures.

The lectionary has cut our first lesson off before Sarai can be named, perhaps because in the very next verse, Avram takes Sarai and Lot along with his possessions, as though they too were also possessions along with the “goods” he acquired in Haran. Or maybe the verse is excluded because it spells out—more clearly in Hebrew than in English—that those possessions are all the persons he has “acquired”—not people and possessions, but people as possessions. Abraham’s patriarchy is rooted and grounded in slavery, sanctified in the text and by the god of this text. Abraham’s house will become great in number, in part, because of the fecundity of his slaves, some of whom he will undoubtedly impregnate himself. Because that is how slavery works and we ought not pretend that biblical slavery was some holy beneficent enterprise.

So then, is this story useful for anything other than asserting a divine claim for patriarchy? Is there a living word here? Is there a blessing to be had that is not nationalistic or steeped in patriarchy? Responsible biblical interpretation has always called for more than simply attempting to imitate an ancient text in our contemporary context. For example, most ancient and contemporary readers understood that incestuous sibling marriage was something best left behind in this text. While on the other hand, the founding fathers and their slaveholding cronies wanted to hold onto the patriarchal promise of wealth to Abraham that explicitly included slaves. Most folk have since let that go, but not all. What then is left in the promise if we let go of the patriarchy, androcentrism, misogyny, and heterosexism in the story, and the whiteness that is so often spackled onto it? A paradigm for leaving behind the things we need to let go.

In the text, the Living Loving God says: Get-you-gone from your country and your kindred and your father’s house…” Abraham has made his journey. His story and the story of his descendants and their nation-building have been told. Today let us focus on Abram’s personal exodus from the household of his father and what that may have signified for his family, those present in and those absent from the text, and what that might just mean for us.

Get-you-gone from your country and your kindred and your father’s house…”

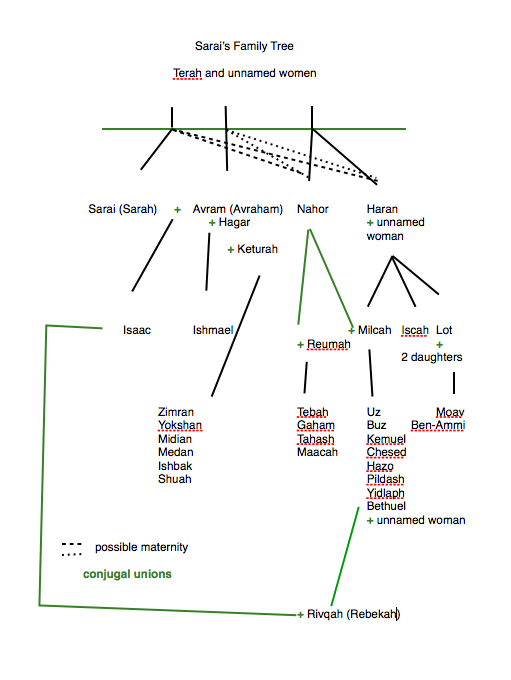

Abraham’s father’s house was rife with incest, but far too many preachers hesitate to use the word—even when acknowledging that Sarah and Abraham have the same father. Abraham and Sarah may well have been products of incest themselves, so common was it in their father’s house. Their mothers are unidentified so we cannot know. What we can know is that Abraham’s brother Nahor had children with his niece Milcah, the daughter of their brother Haran. [Abraham, and his brothers Nahor and Haran shared both parents.] Bethuel, Laban and Rebekah would come from that line descended from Milcah and her uncle.

Though Abraham eventually leaves his father’s house, some of his father’s values stay with him; he insists his son Isaac must marry a woman who is also their relative. In a later story Lot will father children with his daughters. The text will blame the daughters but a womanist reading of the text interprets it through the experiences of victims of sexual abuse who are blamed for their victimization and often charged with seducing the men, sometimes their own fathers, who rape them. Lot left the house of his grandfather, but he didn’t go far enough.

Get-you-gone from your country and your kindred and your father’s house…”

The house of Abraham’s father represents all of the social and sexual dysfunction that would keep Abraham and his parents and partners and their kith and kin, descendants and dependents from living and loving freely and fully. It will take Abraham a while to put the sexual ethics his father’s house behind him, if he ever does. Abraham’s family’s sexual ethics were rooted in patriarchy. Patriarchy resides in his father’s house, though it was not conceived there. Motivated by fear but made feasible by patriarchal reasoning, twice or once in two different tellings, Abraham sells Sarah to a foreign king for his sexual use—including in this chapter—and it takes an act of God to get her back. At some point after leaving his father’s house, Abrahams marries again, Keturah, a woman of his own choosing, a woman who is not from his father’s house. I would like to think that union marks a new beginning for him, a step towards the promise and blessing.

Sarah too is a product of patriarchy and women can and do subjugate other women and sometimes men under patriarchy’s dominion. Sarah employs the lessons she learned in her father’s house against Hagar and, to some degree, against Abraham. Sarah will seize the body of a girl she considers her property and subject her to physical and sexual violence and a forced pregnancy while turning the tables on the husband who sold her for sheep, camels, donkeys and human chattel. Later, her abuse of Hagar will be so violent, so oppressive, that it is described with the same word that Exodus uses to describe Egyptian oppression and affliction of the Israelites, a word that includes rape as one of its primary meanings.

Sarah and Abraham are not the only folk who have needed to leave home to become fully who they were called to be. Sarah and Abraham are not the only folk who have had to leave ancestral and familial teachings about sexuality and gender behind. If we take this lesson to heart we too will leave ignorant, willfully ignorant, and harmful sexual ethics and practices behind. We don’t preach polygamy or incestuous sibling marriages as normative simply because they are in the text. There is no reason to preach ancient Israel’s ignorance about human sexuality, orientation, gender construction or performance as normative either. We can begin to talk about blessing all of the peoples of the earth when we understand them to be equally blessed without regard to gender or its performance and no person is forced into a union against their will.

This text also teaches us it may take some time to be able to leave the house of patriarchy and all that comes with it behind. The passage states: Abram was seventy-five years old in his exodus… The text describes Abraham’s departure from his father’s house as his exodus, using the same word that will describe the Israelite’s liberation for Egypt. Based on Isaac’s birth narrative where she is ninety and Abraham is one hundred we can also say Sarah was sixty-five in her exodus from her father’s house.]

In our lesson, God does not call Abraham to leave the house of his father until he is seventy-five and Sarah is sixty-five. In our world, some folk spend their entire lifetimes trying to figure out how to leave the hopes and hurts, dreams and schemes of our past behind so we can live into who we are called to be. A person can spend a lifetime putting abuse and trauma behind her, unlearning destructive patterns, responses and behaviors, and relearning how to live and love as a whole and healthy person. Life lessons take a lifetime to accrue and Abraham needed seventy-five years before he could draw on that account. However since Abraham lived to be one hundred and seventy-five according to the story, he had another hundred years, an entire lifetime to live into his fullest self, apply the lessons he learned, make mistakes along the way and try again. Perhaps one lesson we are to learn from the length of Abraham’s days is you’re never too old to leave behind that which will not bless you.

Get-you-gone from your country and your kindred and your father’s house…”

Who is your father that needs to be left behind? Maybe it’s the whole patriarchal system and not your dad. Maybe it’s some of the things your dad says that were passed down from his dad. Whose house are you leaving and what are you leaving behind? While you’re making your list, I’ve got a few suggestions for you:

Leave patriarchal interpretations of the scriptures behind in the house of patriarchy. Maybe leave the androcentic lectionary behind as well along with the idea that adding a few more stories about women is good enough. Leave heterosexist biblical interpretation behind in that father’s house. Leave the sanctification of whiteness and refusal to examine its privileges behind in that house. Leave any theology or biblical interpretation that does not lead to the full humanity, liberation and just treatment of any human person behind. Leave biblical literacy behind. Leave willful ignorance of the complexity of scripture behind. Leave predatory preachers behind. Leave kindergarten theology behind if you’re not a child. Leave using the name of God to harm God’s children behind. Leave those things that don’t lead to life, health, wholeness and justice behind and don’t look back.

And you will be blessed, and your name will be blessed and all of the families of the earth will be blessed.

Bring us out of the houses that imprison us, that we may leave behind those things that will hinder us, that all peoples may be blessed in your name. Amen.

Leave a Comment