Is not this the carpenter, the son of Miriam called Mary and brother of Ya‘akov called James and Yosef called Joses and Yehudah called Judas and Shimon called Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?” And they were scandalized by him.

Jesus is simply scandalous. More than notorious or shocking, eskandalizonto in Greek means to offend, to drive away, to force to stumble, to push into betraying or deserting, to cause to sin. Some people love Jesus, particularly what he does for them. And in the previous chapters in Mark he has done extraordinary things for ordinary people. But at the same time some are deeply troubled by Jesus, especially by what he says. It’s not easy being a biblical scholar in the public eye or a public theologian. Teaching and preaching the scriptures means taking unpopular positions with political implications, challenging cultural norms, systems of power and prestige and offending somebody sometime – or you’re not doing it right. It means being accused of all sorts of things, few of them true and it means that scandal of one sort or another is never far away – especially in the case of Jesus and those who follow him, imitate him – that’s what a disciple is, one who imitates a teacher with mathematical precision. And there is a price to pay for scandal: marginalization, and in the case of Jesus, abandonment, imprisonment, assault, execution.

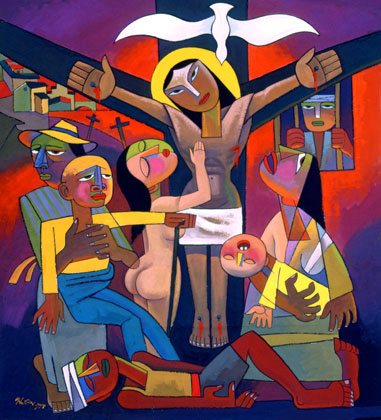

The very humanity of Jesus was a scandal: The Gospels remind us continually that the Messiah was fully human: He was woman-born, his body experienced hunger and thirst and exhaustion and pain and death. Even his post-resurrection body was tangible and capable of digestion along with walking on water and through walls.

The child conceived in holy mystery, whose tiny human heart beat underneath his mother’s heart emerged from his mother’s womb in blood and water as did we all. He was the Son of God, the Son of Woman and a Child of Earth: mortal, frail, embodied, human. To be human is to be carnal, fleshly. For millennia Christians have struggled with this dimension of Jesus’ nature. Some have done away with the human aspect of the Incarnation altogether, and have been properly condemned as heretics. Others turned to Greek philosophy to interpret Christianity and concluded that the body and all its functions are lower than the spirit and its possibilities. Sometimes this spirit/body dualism is expressed in terms of good and evil. But we are wholly God’s good, very good, creation. We are created in the image of God, not in spite of our bodies and their possibilities, but with our bodies and their possibilities. And God became one of us through Jesus.

The gospel writers almost seem to take his infancy and childhood for granted, they were presumably so normal – so human – that they scarcely rated comment. The notable exceptions were his conception, birth and teaching the elders as a child. But of his nursing and burping and diapers and teething and weaning and crawling and toddling there is not a word. Not because these things didn’t happen, but because they did as they did for all of us. He lost his baby teeth, his voice cracked and grew deeper; his Adam’s apple grew more prominent; he grew darker, thicker hair all over his body. And there were other changes. He was a teenage boy, he slept, he dreamed, he imagined, he was human. Dare I say he experimented? He was human. James Nelson in his classic treatise on theology and sexuality, Embodiment asks, “Is the notion of Jesus as a sexual person inherently blasphemous, or at least scandalous?” I say, if we say yes, the problem is with us, not with God’s design and implementation. Jesus was scandalous and people were scandalized by him, by his humanity.

Jesus was like us in his need for human intimacy because he was one of us. He loved, he hurt, he touched, he embraced, he kissed, he wept, he was lonely. He was frustrated when his family didn’t understand him. He was hurt when his dear ones betrayed him. And in his last hours, he didn’t want to be alone to face the coming storm and darkness. He needed human companionship. He cherished his friends and adored his mother.

In our gospel text, Jesus left the place where he healed a woman with a twelve-year vaginal hemorrhage or perhaps she healed herself with her own faith. And he left the place where he raised a girl on the cusp of womanhood from death to life as easily as waking a sleeping baby. He left that place and came to this place, without all of the miracles. This place, his hometown was most likely Capernaum on the shore of the same sea that he had just crossed to perform his most recent miracles rather than Nazareth farther away in the hill country.

He came as biblical scholar and Torah teacher and gave the d’var Torah, (the word of Torah) in the synagogue on Shabbat because he was an observant Jew and did not see his ministry as something other than Judaism. His teaching was amazing, astounding, provoking his hearers to ask where did he study Torah? Who was his rabbi? How could this locust-eater from the desert, as Khalil Gibran would later say, teach like this? And it seems no matter how often folk exclaimed over his teaching, each time he taught; he surprised them all over again. I want to know, what did he teach this time? And why didn’t the gospel writers share his teaching with us this time?

And the people in the synagogue asked how can the same man be both a master teacher and a miracle-worker? Isn’t that just too much giftedness for one man? And because this was his hometown they knew him, they knew his people, they knew his mama. They knew the stories about his daddy – that he might not be his son and perhaps that’s why he didn’t stick around. Joseph disappears from the gospels during Jesus’ adolescence, those difficult teen years and the text does not say that he died. They knew his sisters and brothers by name (their Hebrew, Jewish, names, not the Greek names that have replaced them) and maddeningly to me – the gospel writers still to do not tell us the names of Jesus’ sisters, let alone how many of them there were.

And perhaps, because they knew him, knew where he came from, knew that he was no different from them or at least ought not be any different from them since they all came from the same place, they were scandalized by him, offended by him and rejected him.

This wasn’t, I’d like to suggest, a rejection of Jesus as the son of God; this was a rejection of the local boy who made it big. This was sociology, not theology. Who do you think you are? I know who you are and where you came from. You came from the same place I did. Why do you get to be famous? I came from the same place as you. You’re not special. You’re just like me and I’m not special either.

There is something about the hometown crowd, in big cities and small ones. Sometimes they do celebrate the local girl or boy who has made it big. But in the case of prophets, Jesus says there is no honor to be found at home. How can God speak through such an ordinary person? A person I know is flawed. I remember when… We have these ideas about who can be God’s messenger: men, white men, heterosexual white men, with long beards and robes, projecting our notions about race and gender and sexuality onto the text. So many think of Charlton Heston but not Harriet Tubman or Toni Morrison or Maya Angelou when we imagine prophets. We don’t think to look to our children for a prophetic word, not always to our elders, especially when they are no longer strong and vibrant, to people whose bodies don’t work like ours, or to people who don’t live and love like we think they ought. [I have to say here that I am guilty of this, thinking that today’s guest musician must be an adult, and I was wrong and happily so! Thank you Abigail, for sharing your gifts with us.] All of the biblical prophets are larger than life in the text, but they were just women and men from home towns where folk scratched their heads and said “How can Yocheved’s daughter and son both be prophets? Please! I remember when they were children…” Of course Yocheved’s daughter and son were both prophets, Miriam and Moses.

They took offense at him. They were scandalized by him. The people in their hometown, knowing Jesus and his family and stories that we’ll never know about them said, I just can’t believe this is the guy everyone is talking about, but he sure is some kind of slick preacher. Their disbelief in Jesus, in his ability to do miracles that they couldn’t do and to interpret the scriptures in ways that they could not was an extension of their disbelief in themselves. They did not meet him with the faith of the bleeding woman or grieving father and as a result, Jesus was unable to do the miracles in his hometown that he was able to do in other places. This is a hard text for me, the idea that Jesus is limited by other people’s disbelief, by my disbelief. So I pray regularly the line from another Gospel story: “Lord I believe, but help my unbelief.”

There is so much irony in this text. They, the faithful folk, the Jews in the pews – and we – are why God became human, woman-born. This is, I think, the true scandal of the Gospel, the Incarnation. Those of you who have taken to reading my sermons online, bear with me because I need to repeat some of what I said last week. The scandal of the Incarnation is the scandal of the human body in all of its forms, genders, expressions, orientations, nationalities, ethnicities, abilities, limitations, communicable diseases, poverties and, the scandal of the human condition from mortality to mental illness. I see the scandal in today’s Gospel in terms low self-esteem and holding others in equally low regard. Nobody from our hometown has any right being famous, powerful, respected by important people, recognized for making a difference. I can’t put my trust in this guy from the old neighborhood. Even if he did do all those miracles.

Let’s face it, if folk wouldn’t believe in Jesus when there were other folk saying he healed me, he raised my child from the dead, how on earth are we going to get a committee together to do the work of the church? How can we pursue our calling and fulfill our vocation if none of the people who know us best believe in us? If we have a hard time believing in ourselves? Look to Jesus:

Here he is in our text with the family that has accompanied him in the Gospel for these past two months, caring for him, worrying about him, scolding him and occasionally getting in his way. But they are here with him. Every one of them won’t be with him every moment. But they won't all abandon him. In his most desperate hour, his mother will stand by him and with him, at the foot of his cross. Two of his brothers will carry on his work in his name and give up their own lives for his Gospel.

And for those desperate few hometown folk willing to believe that the boy down the street had the power to touch, heal and transform lives, their faith in him was justified. He did heal them. They were small in number but they bore witness to the possibility of transformation of those who could not let themselves believe in a human, common, familiar Jesus. He marveled at their unbelief and he kept on teaching, kept on serving, kept on healing. Jesus did not stop doing what God called him to do. Not even death stopped him or slowed him. Even when those closest to him did not believe, doubted him, abandoned him, he did the work God sent him to do.

This Gospel is that God’s concern for the woman-born was manifested in God, Godself, becoming woman-born, for the redemption and liberation of all the woman-born from fear and from death itself. Yeshua the Messiah, the Son of Woman, came to seek out and save the lost and to give his life as a ransom for many. Amen.

Leave a Comment